Intimate Constellations/Constellations of Intimacy: An Exchange on Navigating in Collisions | Mathias Danbolt and Ester Fleckner

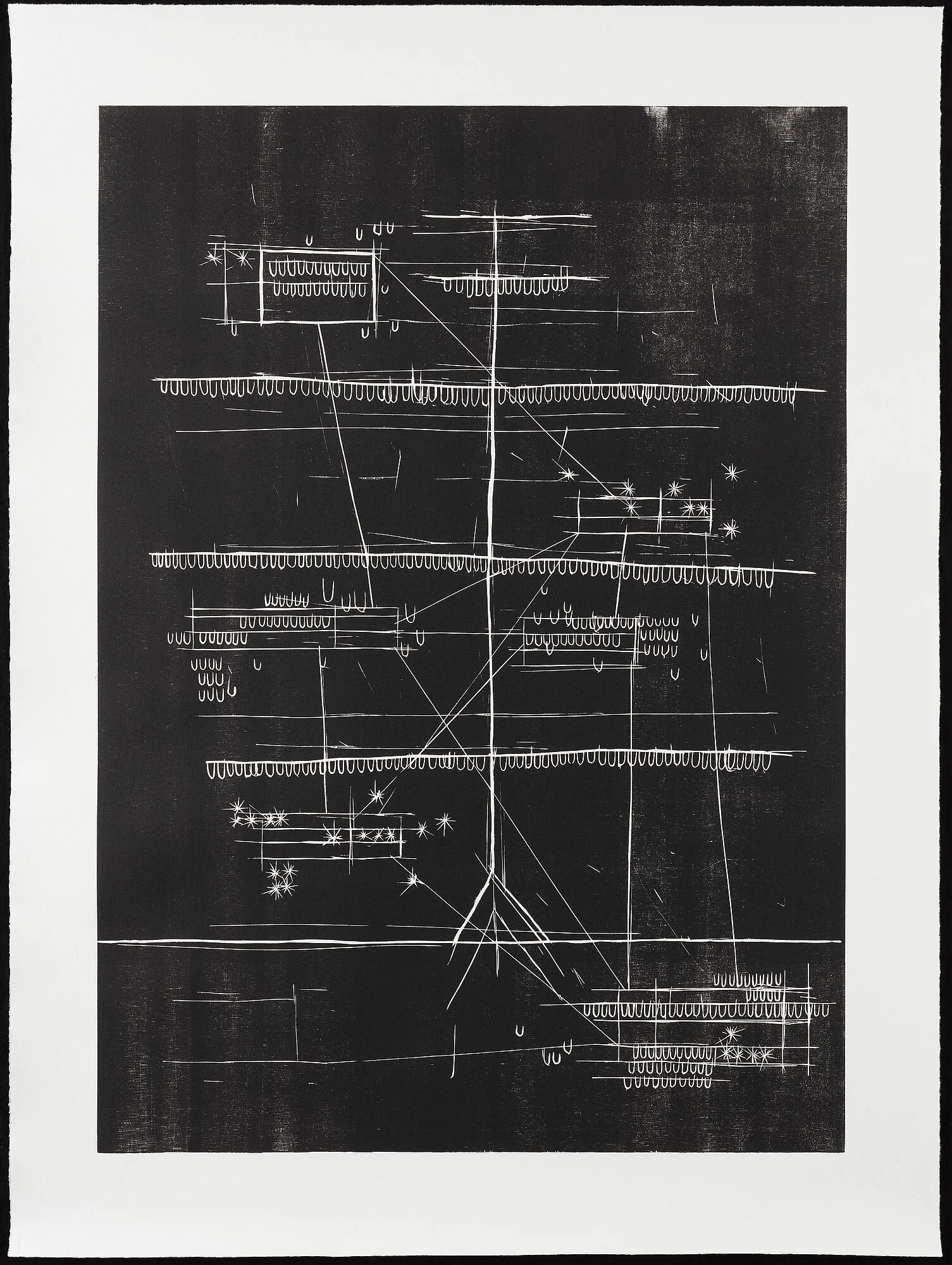

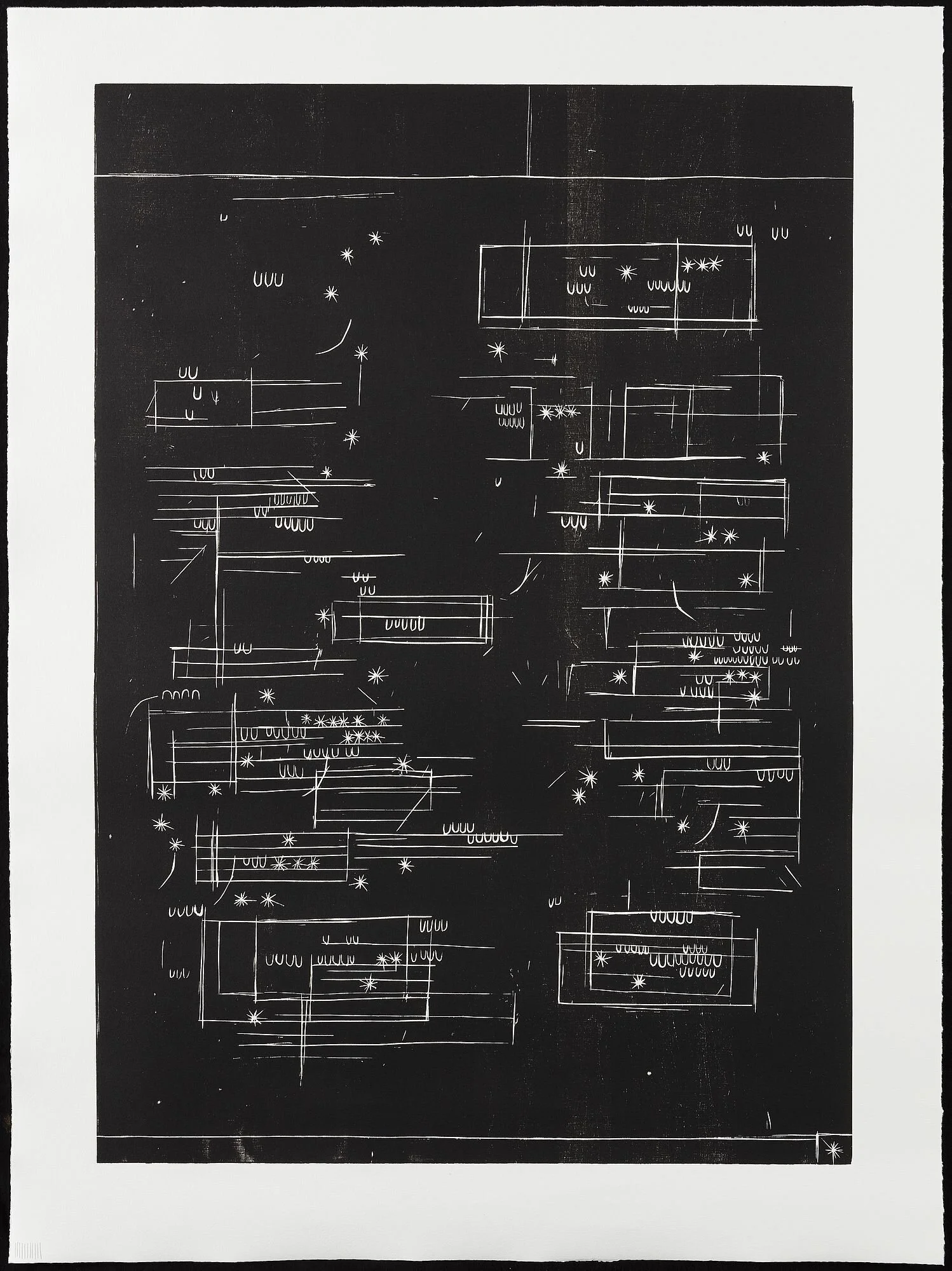

Figure 1: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, flyer (English version), 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 74 x 48 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

1.

Relation. You talk in a way that I don’t know but that I’m missing. You talk about belonging differently. I bike through the city with my eyes closed, or almost. I think about images one can recognize oneself in or not. I think about family trees. And having read that it demands synchronicity with the patterns and rhythms of a place to feel that one belongs. I want to have a relation to you and understand that we already have one.

I keep returning to these words as they were the ones that brought us together, properly at least. They made me realize that I wanted to have a relation to you, although we already had one. I might not have been the “you” that occasioned your text, but standing on the street in the rain, reading the print taped to the gallery window, I knew that this “you” had room for me as well.

The gallery was packed by the time I arrived, the window cloudy by the heat of bodies. A room of other yous. Inside I got lost in your large woodcuts pinned to the walls, with figures that made me think of family trees and other trees, and about being in and out of sync with the patterns and rhythms of the place.

Consider this a love letter in response, a fumbling and tentative one, where voices of others collide or join my own in an attempt to establish that relation that is already there. Like the letter I received that day on the street, I put it here for all to read.

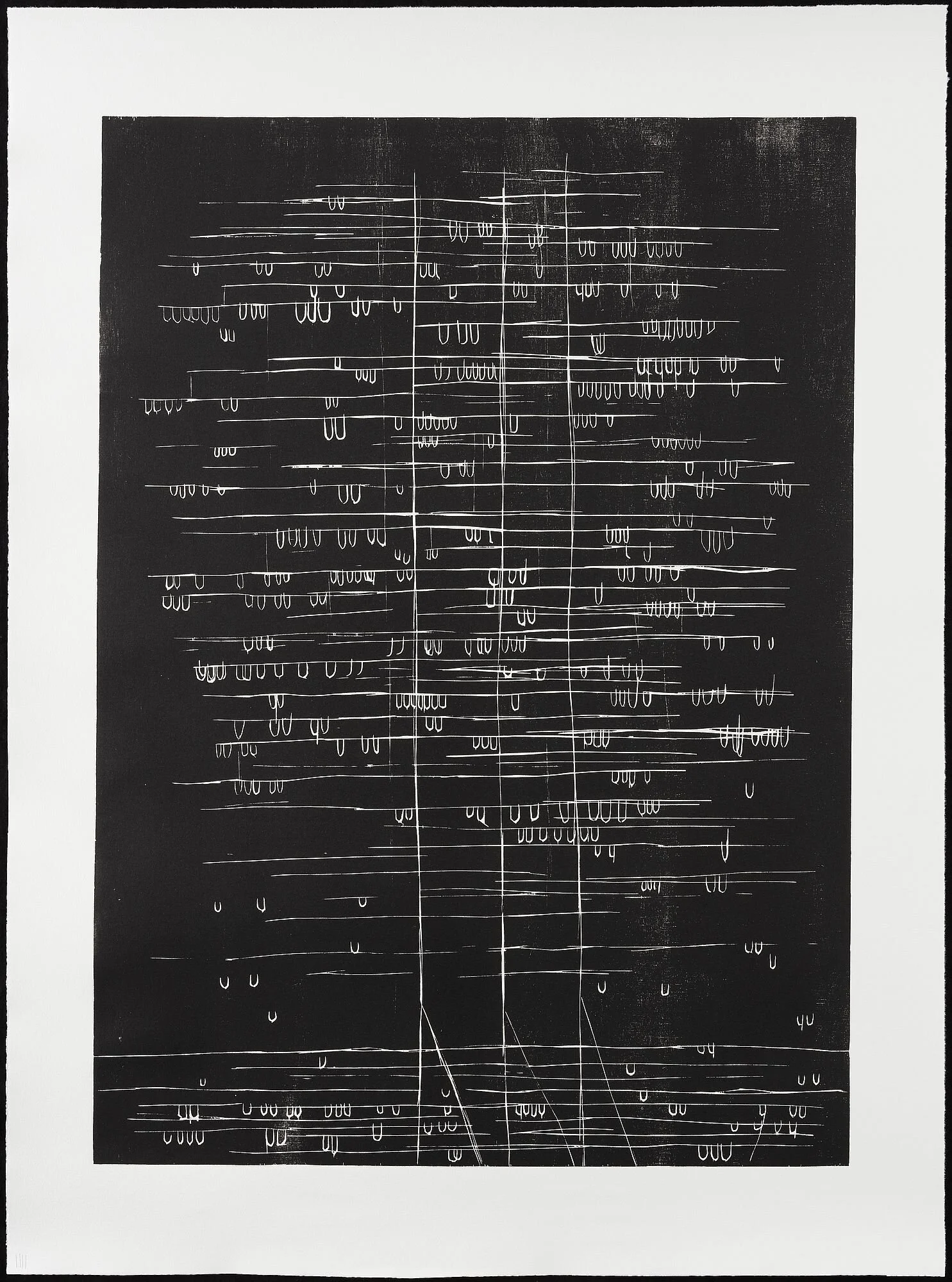

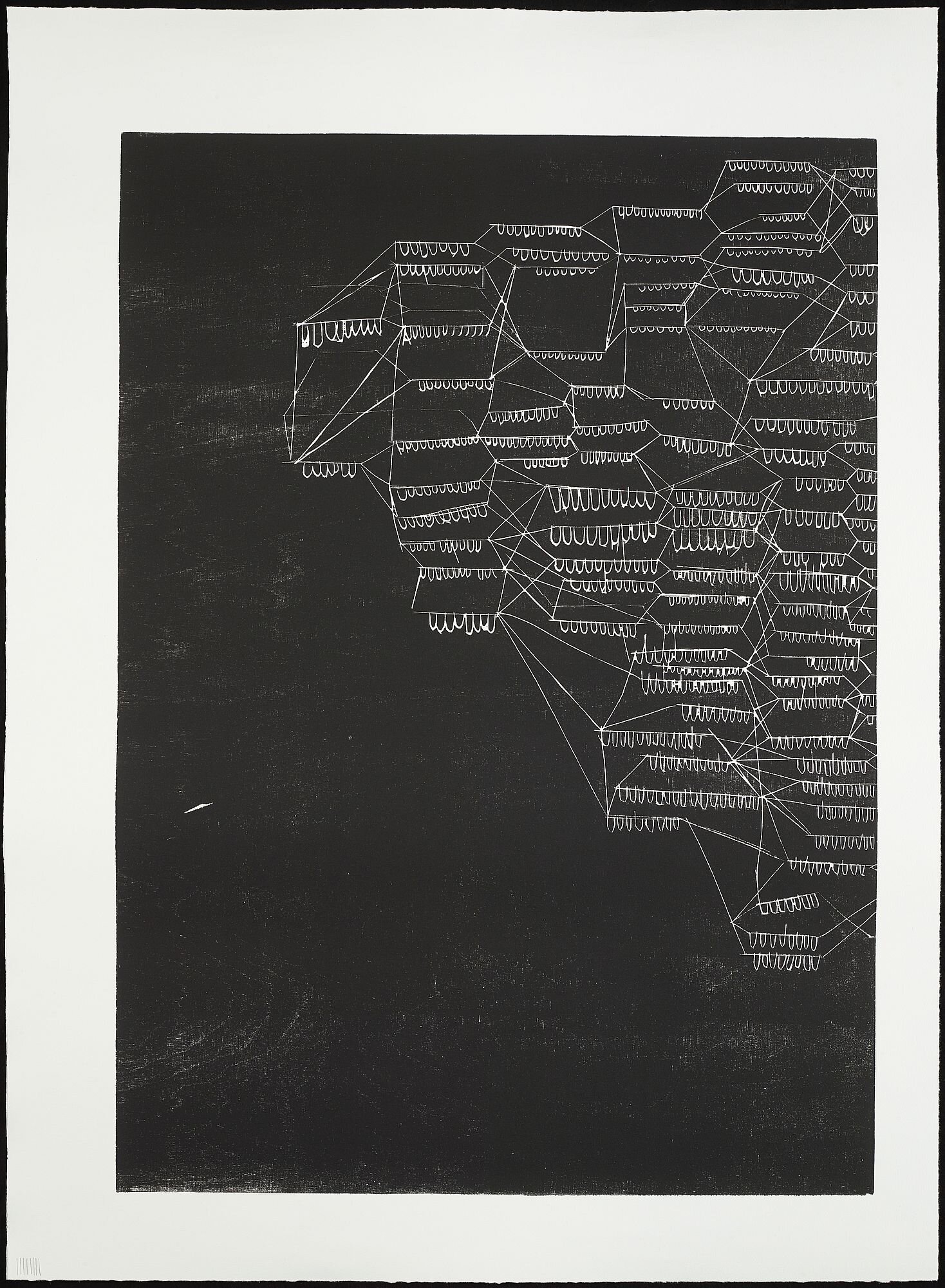

Figure 2: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 9, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

2.

A close friend tends to arrest me when I reply to his questions of my emotional well-being by talking of an artwork I have seen or a book I have read. He suggests that it is my way to avoid confronting negative feelings – anger, loneliness, sadness. He might be right, but I tend to think of it as the equivalent of how other people, in response to my questions of their well-being, steer the conversation into a discussion of their partners and kids. Who decides the line between sublimation and alternative object-choice? Why can’t I be allowed to talk about the relational companions that inform and shape my well-being without being policed for diverting attention from myself?

When I say I’m an art- and book-lover, I don’t mean it metaphorically. My desire for your woodcuts in the series I Navigate in collisions (2014–) go beyond the realm of professional “interest.” After that first encounter, I knew I had to think with them, live with them, write to them, write with them. Their form informs my well-being.

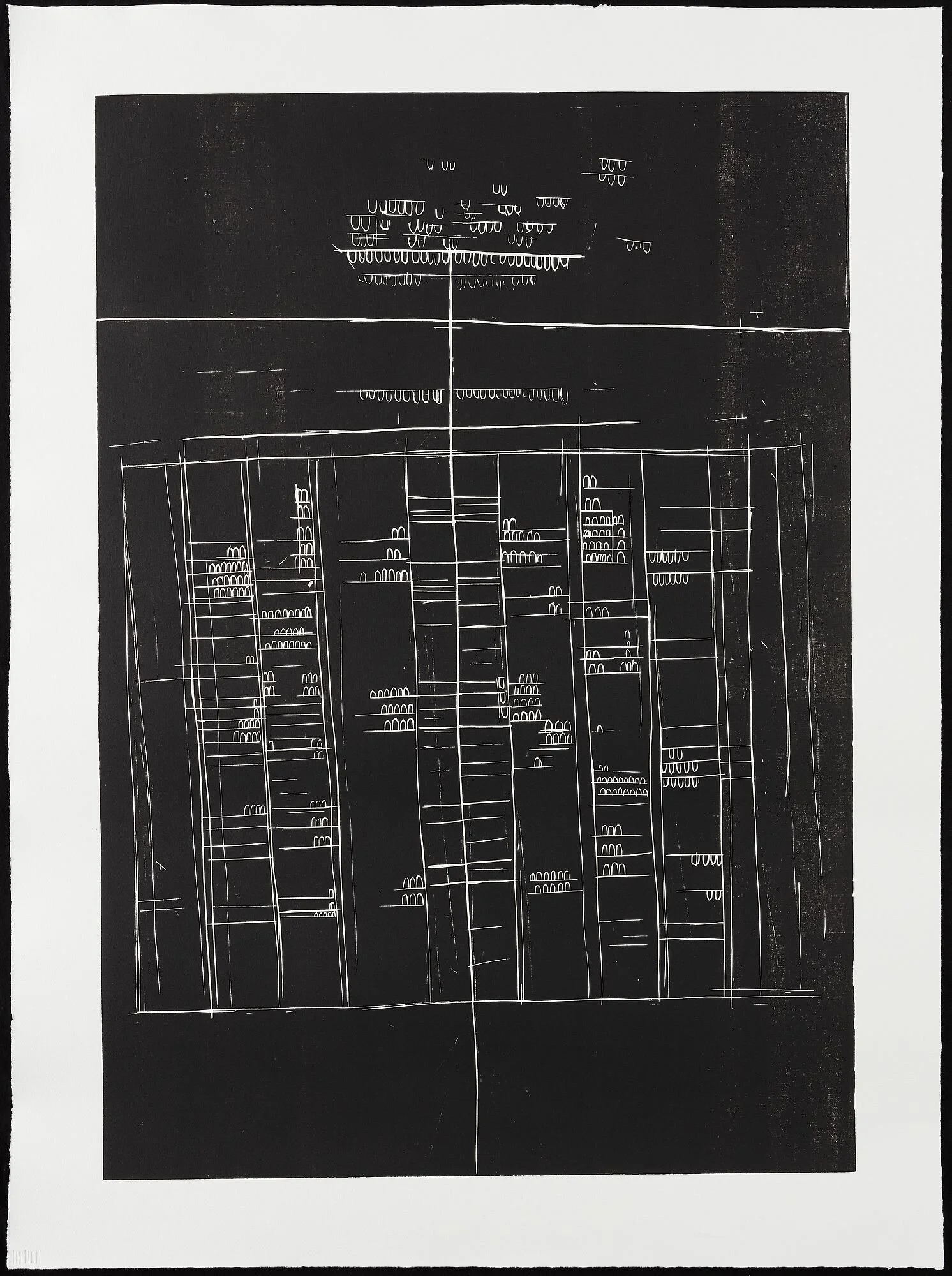

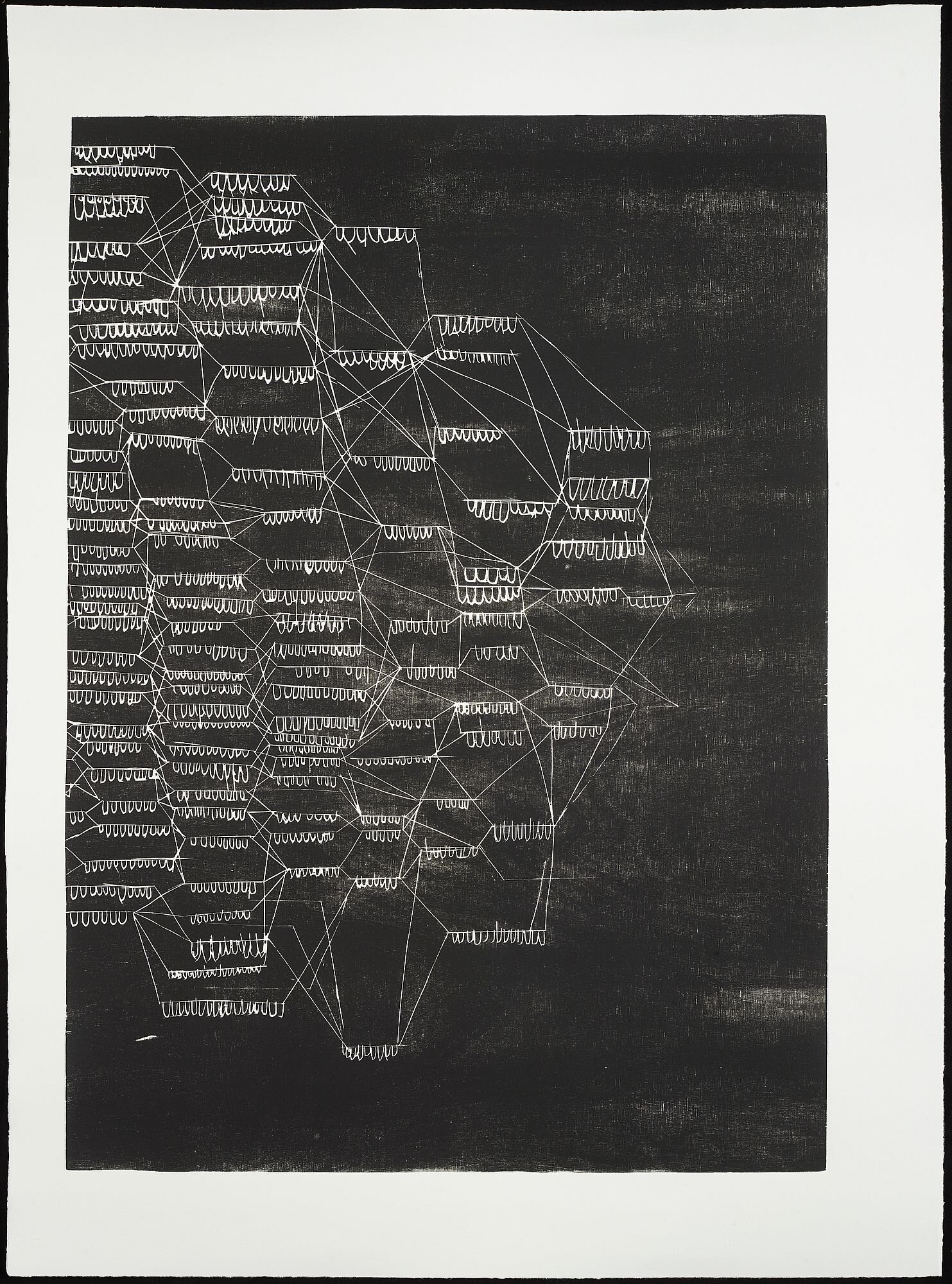

Figure 3: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 2, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

3.

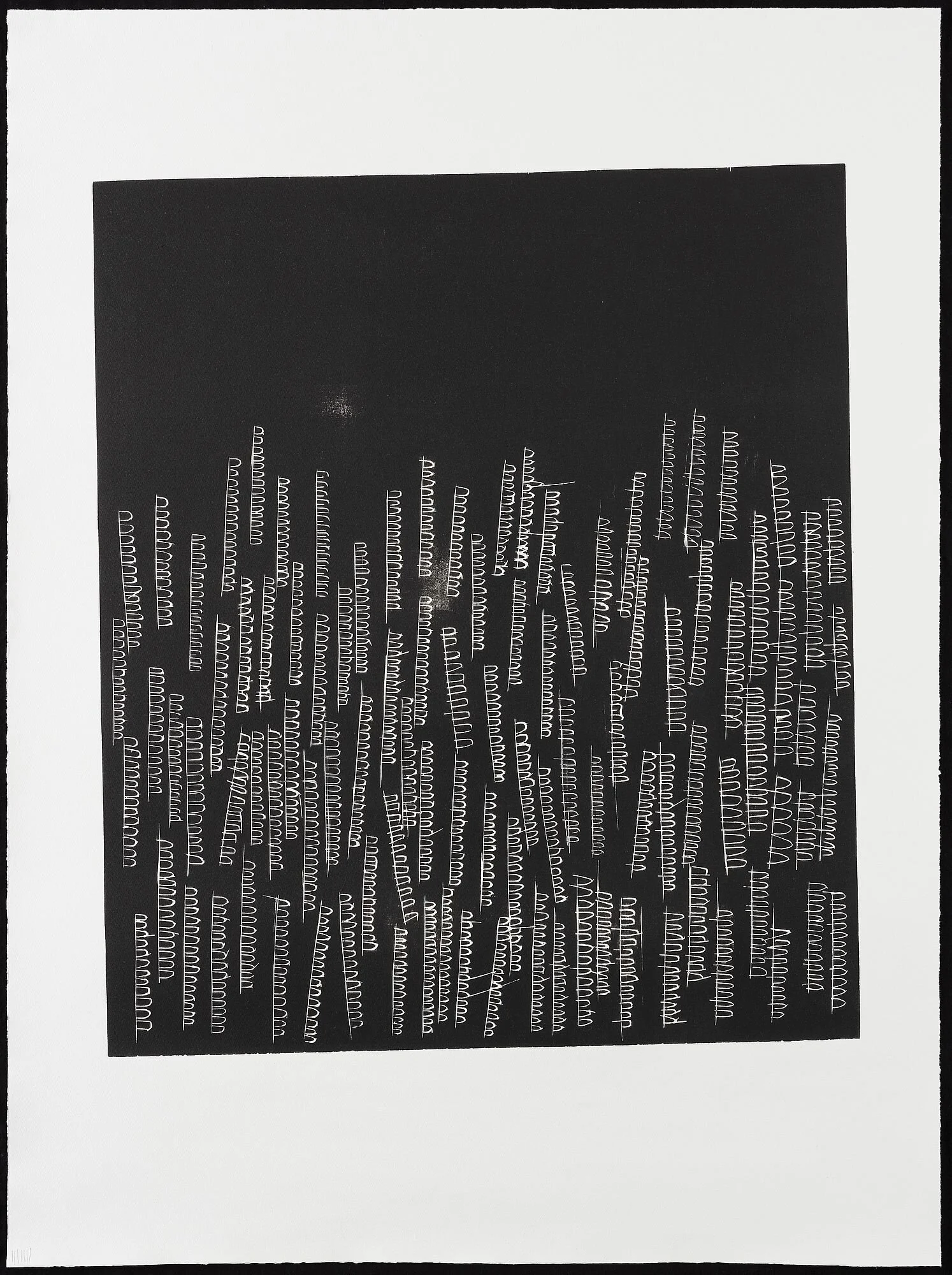

A white structure stands out from an uneven black background. The lines are sharp and clear but rickety enough to call attention to the embodied act of a hand having worked the wood. A precarious architectural structure balances on a scanty horizontal road. An electrical tower? Antenna? A ship’s mast? A tree? A series of U-shapes hang like bats from the parallel beams affixed to the trunk. The U-forms look like letters, like leaves, like breasts, like clits, like dicks, like clit-dicks, like friends, like lovers.

These intimate constellations of lines and forms chart alternative constellations of intimacy. That’s what I see. That’s what they are to me. Like a map I can’t quite decipher, they point to a territory I have a hard time fleshing out but that feels fleshy enough. These patterns of strange connectivities work as a counteragent to the poverty of my imagination in finding ways to chart and value relations that do not conform to default modes of companionship and attachments, like the partner I don’t have, and the couple I’m not in.

My impoverished imaginary is not of my own making. It is a result of navigating through a world where compulsory coupledom marks the pathway to a better good life. I need other lines to follow. Your prints lead me away from the conformity of my desire and my desire for conformity that is and is not my own.

“I LOVE THE UUUUUUNCUT CONNECTIONS” it says in Danish below the bottom branch of the tree. I’m trying to respond to your quest for unabridged connections, as these notes jump and bumb between the concrete and the abstract, the structural and the specific, the conceptual and the personal. But just as the words in your prints are crossed out after having been carved, I admit to having cut out words as well.

Figure 4: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 3, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

4.

A few years back I received a call from my mother. She phones often, usually just to check in, and to give me an opportunity to check in on her, like many of us, I guess. Her voice dances awkwardly, a family tree is bugging her. An uncle I have never wanted to know is putting together a family tree for a book and he wants to get the latest update on our marital stands. My mom wants to know my opinion. My brothers are married and have kids, their rankings are beyond doubt. My mom knows that I’m not the marrying kind. Given that at the time of the conversation, I had lived with my then boyfriend for years, she wants to know whether she should ask my uncle to put my partner’s name alongside mine on the tree. We both know that the presence of two men on the same branch is not something that that part of the family appreciates. I sense my mother is eager for me to claim that our relation should be inscribed and recognized. The family is her activist ground, she enjoys shaking up stiff branches of traditionalists. I appreciate her gesture but kindly ask to stand on my own. It is less the fact that my relationship is falling apart that motivates the refusal. This just isn’t my sort of tree. It is trimmed and pruned so violently and selectively that it feels barren and dead. If there is no room for wild buds and cross-over branches, suckers and lateral sprouts, I don’t want to be part of a forest. I will rather be a dead-end stub, than pass as the wedded couple we never wanted to be.

Figure 5: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 1, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

5.

I don’t usually read naked, and especially not in public, but a friend had brought me to some hot springs north of San Francisco where clothing was optional and I didn’t want to be stodgy. Engulfed in Laura Kipnis’ Against Love: A Polemic (2003) I don’t see the cute guy standing right in front of me reading the cover of my book before he asks

"Against Love? Huh, what’s that about?"

Confused and startled, I go for the soft version."It is an essay that asks why love has become something we cannot not want, so much so that just the thought of claiming to be “against love” is equivalent to be seen as embracing evil. By approaching love in the same way one would approach one of those sectarian religions that has no room for doubters, Kipnis tries to open up alternative views of the social organization of intimacy …"

"Uhuh,"

the guy says,"tell me more."

"Well,"

I continue,"Kipnis is skeptical of how modern love organizes us in endless series of couples that we perpetually need to “work on” in order for that love to survive. The book gives a guided tour of the unattractive conditions for modern love in capitalist society, where the protestant work ethic not only propels us to work more than the scheduled hours on our day jobs, but even more on the home front with help of a therapist or two. Before working ourselves to death, she asks whether we instead should work on rethinking the institutionalization of love that is so effective in killing off passion. When finding ourselves caught up in the complex systems of control and surveillance of what she calls the “domestic gulag” (ibid., 52) or when seeing how divorce rates sky-rocket, or when considering how the lines to the therapists’ offices continue to grow, why does it remain easier to envision the end of the world than the end of compulsory coupledom?"

"I got married yesterday,"

the guy blurts out."I'm here on my honeymoon with my wife."

I blush. I had seen the car covered in ribbons and painted hearts in the parking lot. He winks and adjusts his swimming trunks before jumping into the pool.My friend who hasn’t heard our conversation comes over and compliments me for having scored so quickly. I tell her it is the honeymoon guy. A half hour later he joins me in the hot pool, eager to hear more about the book, about me, about love. The more he flirts the gloomier I get. When his wife arrives, he jumps up and leaves the pool, closing me off like a boy caught by his parents with a porn magazine. As psychoanalyst Adam Phillips notes in Monogamy, “Two’s company, but three’s a couple” (1996, 94).

Figure 6: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 4, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

6.

Love, love, love, love, love, love, love, love, love.

All you need is love, all you need is love,

All you need is love, love, love is all you need.

There’s nothing you can know that isn’t known.

Nothing you can see that isn’t shown.

Nowhere you can be that isn’t where you’re meant to be.

It’s easy.1

I’ve never got the Beatles, specially their anthem to the Empire of Love. The thought that there is nothing we “can know that isn’t known” and nothing to “see that isn’t shown” makes me numb. If love demands that I should accept that this is it, this is where I’m “meant to be,” then I need a hell of a lot more than love.I always feel a perverse sense of enjoyment when finding others who are as cranky as myself when it comes to love, people who make me feel less of an “affect alien” in my paranoid soundings of the world (Ahmed 2010, 54). Encountering philosopher Klaus Theweleit’s acerbic discussion of this wedding song, as he calls this the Beatles-tune in the book Object-Choice (1994), was like being embraced by a friend.

“All you need is love” was written and performed by the Beatles for the “telecommunications marriage” between the antipodean hemispheres on June 1967, when BBC set up “the first satellite link-up for a live television transmission from one side of the planet to the other,” Theweleit explains (1994, 1). Since that day in 1967 the West has sought to broadcast LOVE “twenty-four hours a day around the globe,” he continues, in the manipulative hope that the rest of the world would “cast itself into the longing arms of West-love” (1994, 2).

For democracy there must be love, some says.2

For democracy there must be West-love?

No.

In democracies love is never just a four-letter word.

Figure 7: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 6, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

7.

“Because erotic life rearranges the world it is political,” Adam Phillips writes in Monogamy, and continues, “every form of erotic life makes a world. Our monogamies, our infidelities, our promiscuity go on in a world of other people, and cannot help but make a difference to the ways they organise their lives” (1996, 72).

This is one of the obvious connections between the erotic and art. The rearrangement of the sensual world brings art into the sphere of the political. Every esthetic practice makes a world. It better be a better one.

Did love create all these couples around me? Or did the couples produce love as their origin?

Is love, like gender, a performative? A copy of a copy with no original—a script that acts us out as we try to act within its framework of recognition and intelligibility (Butler 1990)?

If love is a script that we cannot not follow—a rite de passage to proper subjecthood—how can I know whether the love I might fall in is mine?

A frightening realization: All of us are married, if not with a partner, then with our parents.3 The fact that my parents are the ones who in the case of my sudden death have the legal access to my body, my belongings, my left-overs from life, and not my friends who know my body, my belongings, my life so much more intimate, is something that can make me want to put a ring on it. I have friends who have gotten married to divorce their parents.

Some find it cynical talking about marriage in economic terms like these. But I wasn’t the one who decided that marriage should be one of the few ways to break the branches of the family tree and grow with others differently. This aspect is what Adam Phillips misses in his sharp-witted argument about marriage as “fetish” (1996, 83). According to Phillips, what “most people need is often simply the name of the relationship, its official title. The problem—or, indeed the pleasure—of marriage is that it can never be called an affair” (Phillips 1996).

I wish this was true. But marriage is not a fetish, even though it is that too, of course. The fact that we arrive to this social institution with so radical different backgrounds, subjecthoods, possibilities, and potentials makes marriage something many of us cannot not want. But I want more. Other fetishes. Other redistributive affairs.

Figure 8: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 12, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

8.

I get home from work and find a letter delivered directly to my mailbox, no stamp or mailman involved:

Loneliness can be many things. You can feel lonely, even though you are surrounded by others. It is far from shameful or taboo to start talking about loneliness. Everyone has something to offer, and in an experiment with a famous Danish TV-star, we want to explore how much it takes to invite someone in. […] We are seeking you for our experiment. It will not affect your job or your school.

Email or call on kro@xx.dk or 2246xxxx.

Best regards,

Danish Radio.

Dear Danish Radio

Thank you for getting in touch regarding your search for lonely people in Copenhagen. I don’t doubt that I have something to offer. After all, you note that we all probably have. But I cannot help but wonder: Did you deliver this letter to all the mailboxes in the stairway of my building? Or only to the few of us who have only one name on the door? Thank you for making me aware of the fact that I am one of the only people living alone in my building.

Sincerely,

X

Figure 9: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 5, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

9.

Kjernefamilie. Stjernefamilie. Nuclear family. Star family. The Norwegian words don’t rhyme in English. Sociologist Unn Conradi Andersen’s work on the power of figurations return to me often (2013, 51). I keep being inspired by her examination of families that might be colorful as the rainbow but that are organized not in single arches but like twinkling stars that radiate in different directions simultaneously. In contrast to nuclear implosions, star families enable beams of intimacies and attachments to coexist, without one having to outshine the other.

Anusstjerne. Anus star. The word sounds better in Danish. This term isn’t mine either. I borrow it from an earlier series of your woodcuts. This figure has altered my encounters with stars – those above and those below.

By the way, did I tell you that my ass hurts? Too much information. I keep breaking my writing mentor’s dictum of keeping texts intimate never personal. But who do you tell such things to when you wake up alone, with no one there to see and know the shape and form of your body?

I am working on unlearning my tendency to keep my anxieties to myself while sharing only the joyous and cheerful. How difficult it is to call people when knowing that I’m not good company. How crucial to avoid saving the challenging aspects of one’s personhood to an imaginary significant other. I work on letting anxiety and loneliness shine evenly across different webs of attachment.

Figure 10: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 10, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

10.

What is love?

Baby don't hurt me.

Don't hurt me no more.4

Why love hurts? For sociologist Eva Illouz this isn’t a question. Why Love Hurts is a verdict, one that invites “a sociological explanation,” as the subtitle of her book makes clear (2013). Perhaps I should have taken the fact that I first heard about the book from a love that hurt as a sign of something. Reading it on a bench on the boardwalk above Santa Monica beach, surrounded by perfect-looking couples enjoying the sunset, I am grateful that the hurt left me with this book – and more. Illouz writes:It is now urgent to claim not that our failures of our private lives are the result of weak psyches, but rather that the vagaries and miseries of our emotional life are shaped by institutional arrangements (Illouz 2013, 4).

Modern love is not a particularly lovely configuration according to Illouz. Her story of the shifting conditions for love in “hyper-modernity” is a story of how a “capitalist cultural grammar” has “massively penetrated” the realm of heterosexual romantic love and desire, leading to a “economization of social relationships” and “individualization” of lifestyles (Illouz 2013, 9). Illouz historicizes love, treating it as a “privileged microcosm” to analyze our contemporary society (2013, 7). Love turns strange here, but no stranger than I feel that it is my ordinary suffering she writes about when questioning the effects of the ideals of recreational sexuality and sexiness that govern the field of modern love.Can I really say that my way of navigating across the sexual pastures is any less informed by the codified criteria of sexiness, and its rehearsed cultural codes, than the straight people Illouz studies? Can I truthfully say that my desire is any less shaped by encoded cultural assumptions organized around standardized visual models of attraction? When reading Illouz' discussion of how we, in order to be intelligible to ourselves and others, frame our experiences according to established cultural patterns and institutions, I am reminded of why I am dependent on the esthetic, like your prints, and their potential to cut through and remake cultural patterns.

If Illouz is right in her claim that our psychic interiority and individuality is a less important factor in shaping our lives than the social organization of experience and desire, it is a wonder that we don’t put more energy into establishing new, strange “institutions” that can back up experiences that fall outside of the established forms of organization that the family, marriage, coupledom, and therapists have to offer.

I realize that I have come to use your woodcuts as an “institution” that can corroborate my experiences. Unlike the already established frameworks that help make our experiences intelligible to ourselves, your esthetic micro-institutions, with their bewildering set of cultural patterns and figures, give room for the unintelligibility of myself. Your prints don’t harbor interpretive clarity. They offer maps of estrangement and wonder, intricate codes that gesture toward a cultural organization of bodies and intimacies in ways that is yet to be decoded, yet to come into being, and that read differently depending on one’s interpretive agility.

The disciplinary art historian in me appears from time to time waving a red flag, suggesting that I read too much “into” these prints.

The undisciplined queer theorist in me rebuffs, reminding me that I’m just establishing different meanings by putting the works to use. Attending to the value accrued in use instead of origins and intentions is after all one of the main tenets of queer cultural studies (Doyle and Getsy, 2013). Instead of privileging the act of tracing things back to its roots, we’ve learned to cherish the endless sprouts and possibilities that come from taking and remaking something according to desire and needs. This includes the need to get disoriented, disturbed, disfigured.

Figure 11: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 7, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

11.

At the new year’s party, we are all squeezed together into what looks like a collective body moving in sync with the pumping tunes. Arms and legs, sweat and glitter swirl around. Inside the whirlwind, it feels strangely quiet. In the middle of the mush, I realize that the dancefloor is neatly organized in a series of modular constellations. Like satellites gyrating planets, all dance in small units of two orbiting around each other.

I feel like the debris in space that risk to throw satellites out of track, but somehow my body doesn’t ruin the order of the galaxy. I don’t have the force of the heaps of trash that break up the pending love affair between Sandra Bullock and George Clooney in Gravity (2013). I’m unable to throw anyone into space. Instead, I’m floating freely in the hope that a storm of debris will hit me. But I’m allowed to drift away without any of the satellites taking notice.

Figure 12: Ester Fleckner. I navigate in collisions, (Jeg navigerer i kollisioner), 11, 2014–2015. Woodcut on paper, 101 x 75 cm. Courtesy of the artist, Avlskarl Gallery, Copenhagen, and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. (Photo: Anders Sune Berg)

12.

I find myself cruising through the grids again, thinking about the “architecture of choice” (Illouz 2013, 90) and the normalization of a certain esthetic of evaluation of bodies performed with the swipe of a finger. “Grindr is a technology of loneliness,” I hear myself saying, with the authority of all my scholarly self.

How tempting these words are: “is”, “are”. As if saying a sentence with the proper sense of security will turn my feeling of being grid-locked in a structure of “cruel optimism” (Berlant 2011) into a theoretical-political diagnose. Is this how theories start? In the hope that by magnifying a personal affective dynamic one can make the singular experience cover a territory shared by others?

Theory-making as violent universalizing.

Theory-making as self-help.

As if my endless scrolling down the thumbnails is an act of analysis. Or political resistance.

At a party last week, I met an ethnographer who does fieldwork on Grindr. I had seen his profile online, and he had probably seen mine, but we chatted as if this was our first encounter. When I asked him how loneliness featured in his material, he laughed, as if I had made a joke. He was interested in how new technologies open up spaces for creativity and connectivity, of proximities and promiscuities—in short, for queer modes of use. His digital effervescence effectively blocked my theory of the community of the lonely, my universalized experience of refuse.Yet, I cannot stop thinking about the ways in which form matters. How these orderly grids and patterning of bodies inform the conceptions and experiences of the erotic, the sexual, the passionate. Perhaps my distress stems from the fact that I cannot let go of the feeling that I’m ordering a pizza on these apps. Or that I’m the pizza that is being ordered.

A crisp bottom with a hot top.

13.

I’m a romantic, but only when it comes to politics. I cannot let go of the hope that in creating new constellations of intimacy and new maps of attachments one can alter the world. Or, at least a life.

I know that my desire for a revolution of intimacy might sound retro in a time when mocking left-wing “hippies” and other different-thinking figures have become a public sport. But the embarrassment of not being in vogue seems far less frightening than the prospect of giving up the thought of alternatives to the status quo. In times where the desire for a different political-sexual-racial order keeps being dismissed with such fervent intensity, it might be worth asking, as queer feminist scholar Lauren Berlant does in “’68 or Something”: “What nuclear button does the word utopian push?” (1994, 125)

This diptych of yours is the closest I get to utopia. Not in the sense of a blueprint of how the world should look. But being caught in this beehive, this rhizome, this cloud of attachments where U meets U meets U in an assemblage of virtual intimacies, I get the feeling that everything could be organized differently. These prints function as “an utopian performative” (Muñoz 2009) that gives momentary sense to the bewildering force of shared estrangement.

That is as close as I get to a definition of love.

Or at least something lovely.

Notes

The Beatles, “All You Need is Love”, 1967. Lyrics by John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

The collaborative work on this text started in response to artist’s Carlos Motta invitation to participate in the symposium “The Empire of Love: Alternative Relationships and Other Possibilities” at the University of Gothenburg and Röda Sten Konsthall in 2015, organized in conjunction with Motta’s solo exhibition “For Democracy there Must Be Love” (2015) at Röda Sten Konsthall, Gothenburg, Sweden.

I owe this formulation to my dear friend and colleague Mons Bissenbakker.

Haddaway, “What is Love”, 1993. Lyrics by George Morton and Tony Michaels.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. The Promise of Happiness. Durham: Duke University Press.

Andersen, Unn Conradi. 2013. “Fra kjernefamilie til stjernefamilie. Ekspertenes makt og nettets motfortellinger [From Nuclear Family to Star Family. The Power of Experts and Online Counter-Discourse].” In Å være sammen. Intimitetens nye kulturelle vilkår [Being Together: The New Cultural Conditions of Intimacy], ed. Wencke Mühleisen, 29–53. Trondheim: Akademika Forlag.

Berlant, Lauren. 1994. “‘68 or Something.” Critical Inquiry 21(1): 124–155. doi: 10.1086/448743

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Doyle, Jennifer and David Getsy. 2013. “Queer Formalisms: Jennifer Doyle and David Getsy in Conversation.” Art Journal 72(4): 58–71. doi: 10.1080/00043249.2013.10792864.

Kipnis, Laura. 2003. Against Love: A Polemic. New York: Vintage.

Illouz, Eva. 2013. Why Love Hurts: A Sociological Explanation. Cambridge: Polity.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

Phillips, Adam. 1996. Monogamy. New York: Vintage Books.

Theweleit, Klaus. 1994. Object-Choice (All You Need Is Love …): On Mating Strategies & A Fragment of a Freud Biography. London: Verso.

Notes on Contributors

Mathias Danbolt is an Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. His work centers on the politics of history and historiography in contemporary art and performance, with a special focus on queer, feminist, and decolonial perspectives on art and culture. His work has been published in journals such as Journal of Aesthetics and Culture, Nordic Journal of Migration Research, and Lambda Nordica, and anthologies including Performing Archives/Archives of Performance (2013), Not Now! Now! Chronopolitics, Art & Research (2014), Otherwise: Imaging Queer Feminist Art Histories (2016), Curatorial Challenges (2019), and Racialization, Racism, and Anti-Racism in the Nordic Countries (2019).

Ester Fleckner is a visual artist living and working between Berlin in Germany and Møn in Denmark. Fleckner is educated at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, Denmark and from Goldsmiths University, London. Her work explores language and materials in ways that preserve traces of process and privilege the repetitive labor of trial and error. Inspired by queer methodologies, Fleckner seeks to invert the value of failure, the unfinished, and displacement to arrive at chaotic and intuitive ways of knowing. Fleckner’s most recent solo exhibitions include Pressure/ Imprint at Malmö Konsthall in Sweden (2017–2018), All models are wrong, some are useful at Barbara Wien Gallery in Berlin (2017), and A closet does not connect under the bed at Overgaden Institute of Contemporary Art in Copenhagen (2016). Fleckner’s work has been included in recent group shows at Galeria Municipal da Boavista, Lisbon, Portugal (2018), Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo, Norway (2016), LWL: Museum fur Kunst und Kultur, Munster, Germany (2016), and Schwules Museum, Berlin, Germany (2015).