The Feminine in Abstract Painting Reconsidered | Shirley Kaneda

When I initially raised the notion of the feminine in abstract painting 25 years ago, it was not to construct a new universal, thus replicating monologism, or an equivalent set of signs to balance the lexicon of the masculine. Rather, it was meant to constitute a method of intervention, a way to insert into the discourse of identity and gender that had become significantly literary rather than aesthetic. I had tried to point out certain exclusionary practices inherent in abstract painting, synonymous with Modernism, and how in this pluralistic and confusing time our culture gave way to certain “other” approaches to abstract painting that now seem prevalent despite the long history in which these approaches were already present in some form or another. I termed this the “feminine.” That women seemed to be making the most interesting painting at that time (and continued to in the ensuing years) needed illumination as well as interrogation and further examination. Indeed, as I thought more about the nature and language used to uphold certain dominant beliefs in the practice of abstract painting, it became more apparent to me why women in general were always excluded from this discourse. Since the world is predominantly based on a patriarchal society, the values that are attached to anything are usually masculine. As I argued in this earlier essay, those “masculine” beliefs themselves were put into question particularly as abstract painting became stagnant and “dead”—as it became synonymous with the same ideals as those inherent in the exclusionary practices of Modernism.

"Painting and its Others," as published in Arts Magazine, Summer 1991. Cover image: Mary Heilmann, Mode O'Day (1991). Oil on canvas, 54 x 64 inches.

This essay, entitled “Painting and Its Others, In the Realm of the Feminine,” was published in 1991 in Arts Magazine, whose editor at the time was Barry Schwabsky. It was a product of a conversation I had with Barry about women and painting and how I thought (and still do) that women make distinctive contributions to abstract painting with little recognition. Artists such as Mary Heilmann, Valerie Jaudon, and Shirley Jaffe (Figure 1) had been painting for a long time, but it was only in the early 1990s that their works started to exemplify the concept of the feminine which was both a way to de-stabilize the universalist notion of “quality” and insert an alternative model based on rejected or supposedly inferior notions such as the decorative or the “de-skilled” in regards to hard edge abstraction or fragmentation.[1] These artists’ works were not “feminist” in that their medium of choice could not be understood as having a political content, as in the works of someone such as Judith Bernstein or Judy Chicago, but my assertion was that abstraction was no less capable of addressing concerns of gender and that it was imperative to do so in order for abstraction as a genre to evolve out of the hegemony of modernist criteria. That modernism relied on those values such as singularity, the monolithic, clarity, the authoritative, and so on as a means to distinguish what was deemed as exceptional quality and to legitimate painting most often made by men only led to stasis in abstract painting. My aim was to challenge those assumptions and create a more fluid field of criteria by affirming what were once thought of as marginal approaches.

Figure 1. Shirley Jaffe, Adria’s Green (2014). Oil on canvas, 28 ¾ x 23 ½ inches (73×60 cm). © Shirley Jaffe. Courtesy of The Estate of Shirley Jaffe and Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.

What is the relationship between art (in this case, painting), the feminine, and feminism? From my point of view, the feminine does not stand in opposition, nor is it “other.” The purpose of illuminating such a discourse was to argue that difference is not otherness, but rather it is about constructing a network of signifiers, drives, and meanings that join together and divide in an enigmatic process, consequently invalidating the diametric structure of the masculine/feminine split. The rapid assertion in terms of who is attributing this experience within sexual identity is in fact simply an evasion of its most incisive qualities.

Evidently we are in the realm of the ideological, that is, the place of desire and its rationalization. The feminine has been the property of the masculine hierarchy until the present and has been defined by and denigrated by it as such. By reasserting the feminine as a thing itself, I was attempting to rescue it and propose another set of terms for the construction of a subjecthood and female subjectivity specifically. In order to approach this project one must do this from the principle of the feminine, rather than the masculine, which represents homogeneity, singularity, and equivalence. The point is to reconstruct a dynamic built on symbiotic asymmetry rather than the notions of competitive dialectic in which a set of contradictions vie for dominance. In this sense, Freud’s account of the enigma of the narcissistic woman holds greater potential for feminism than the competing theory of rivalry, which inevitably constructs woman as the object of male desire.

To take this notion further, and the reason why Freud abandoned the theme of the powerful, self-sufficient woman, was because he could not solve the enigma of woman. In his lecture, “Femininity,” he aims to eradicate the opposition between men and women “in favor of bisexuality, a bisexuality that presumably constitutes the whole enigma in what men call “the riddle of femininity” (Kofman 1985). However, the notion of bisexuality is a convenient way to side step the issue of defining woman and her powers. Freud again defines women from a male perspective by using himself and men in general as a model for his theory, and by claiming that males have more bisexual tendencies.

As Walter Benjamin pointed out, the difference between Fascism and Socialism is that the Fascists aestheticised politics and the Socialists politicized aesthetics. The question that has been repeatedly asked since the confusion that has arisen from the notion of the feminine is: are we now to speak of a feminine feminism or a feminist feminine? This is not a word play, but a play of concepts: one conceals and the other reveals, “between the idea of a political identity for feminism (what women require) and that of a feminine identity for women (what women are or should be)” (Rose 2011).

If we accept the view that culture and high art in particular is the site of the ideological, or the struggle of societies’ standards and values, and that there is presently a crisis in our society, a fundamental re-examination of identity for example, then we must be conscious not only of what we say, but how we say it. As I have acknowledged before, the feminine and the masculine are not gender bound. There are masculine women and feminine men and these characteristics replicate themselves in the struggle to produce a feminist art, in which there are masculine and feminine models. The problem that arises in most cases of appropriation of these readymade models is that they are used in non-reflexive modes. In these instances equality becomes reduced to a question of replacing a male figure being (beaten by a cop) with a brutalized female figure. Both are represented using the same vocabulary and the message is seemingly the same: stop brutality. There is no implicit or explicit alternative view proposed by the means of the experience in most cases and the signifier is once again charged with the value of the imagery, which is already recognizable as universal or masculine in its approach. What needs to be emphasized is that if we as women want our experiences and our cultural conditions to be recognized specifically female, then we must claim a position, not as other, but independent of the masculine world and this is to be in favor of a concept of the feminine which would take as many forms as there are women.

Constructing a definition of a feminist identity is more visible in medias other than painting, as we have witnessed in Cindy Sherman’s photographs or in the works of Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger to name a few. But the question remains: what is the relationship of painting to women? Veteran feminist painters such as Judith Bernstein and Lee Lozano who painted male and female sexual organs to “own” and challenge the patriarchy were marginalized for many years. They are now being recognized and “discovered” by the market’s insatiability. Of late, there are women painters who deal directly with feminist issues through figurative imageries of oppression, dominance, abuse, or by appropriating known paintings by men to de-masculinize these visual imageries. Sue Williams has painted penises in the style of Jackson Pollock or Cecily Brown unabashedly paints pornographic scenes of coitus in her otherwise “abstract” paintings. They certainly make their point in the same way that the six o’clock evening news does. But what would be served by the paintings of Williams or Brown? Are we to think that we will become more conscious of gender inequality if we are to witness this in the site of painting? Does this accord a new and more viable position for women painters? Or, as I suspect, does it only tickle the fancy of those male collectors who no longer have to be ashamed in private, but can now hang these paintings proudly in public and be exonerated of their own crimes. Either way, the winner is obviously the patriarchy.

The reason once again is that it does not establish any criteria of its own. Establishing criteria of its own for a tradition as historically determined as painting is not only extremely difficult, it is nearly impossible. Recently there has been much talk and publicity about women painters. Press releases for various exhibitions freely and non-critically use the term “feminist painters” in regard to women painters making abstract paintings. Take for example two recent shows by Carrie Moyer (Figure 2) and Amy Sillman (Figure 3), whose exhibitions ran concurrently in February and March of 2016 in Chelsea. I would argue that rather than naming them as feminist paintings, they are more feminine in ways that I have explicated thus far. The feminine allows for a wide range of approaches and one that does not necessarily conform to any set of given standards. The feminine is much like the real, which is virtual and unformed.

Figure 2. Carrie Moyer, String Theory + Daisy Chains (2016). Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 96 × 78 inches (243.8×198.1 cm). © Carrie Moyer. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Figure 3. Amy Sillman, Back of a Horse Costume×2 (2015–16). Oil on canvas, 75 × 66 inches (190.5 × 167.6 cm). © Amy Sillman. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

Moyer’s works eschew a decorative sensibility that may be understood as feminine, but she undermines the decorative through her clear and critical use of the history and vocabulary of abstract painting as signs, juxtaposed with hard edge shapes creating an unstable field in which contradictory parts exist together to reconcile the apparently incompatible. Here, the intellect and the sensuous, male as the mind and female as the body exist not as two qualities in a hierarchical system, but as complements within a situation in which both are predicated on one another. Rather than hinge on exclusiveness, the work’s open-ended quality seeks to expand the subject instead of narrowing it down to a masculine singularity.

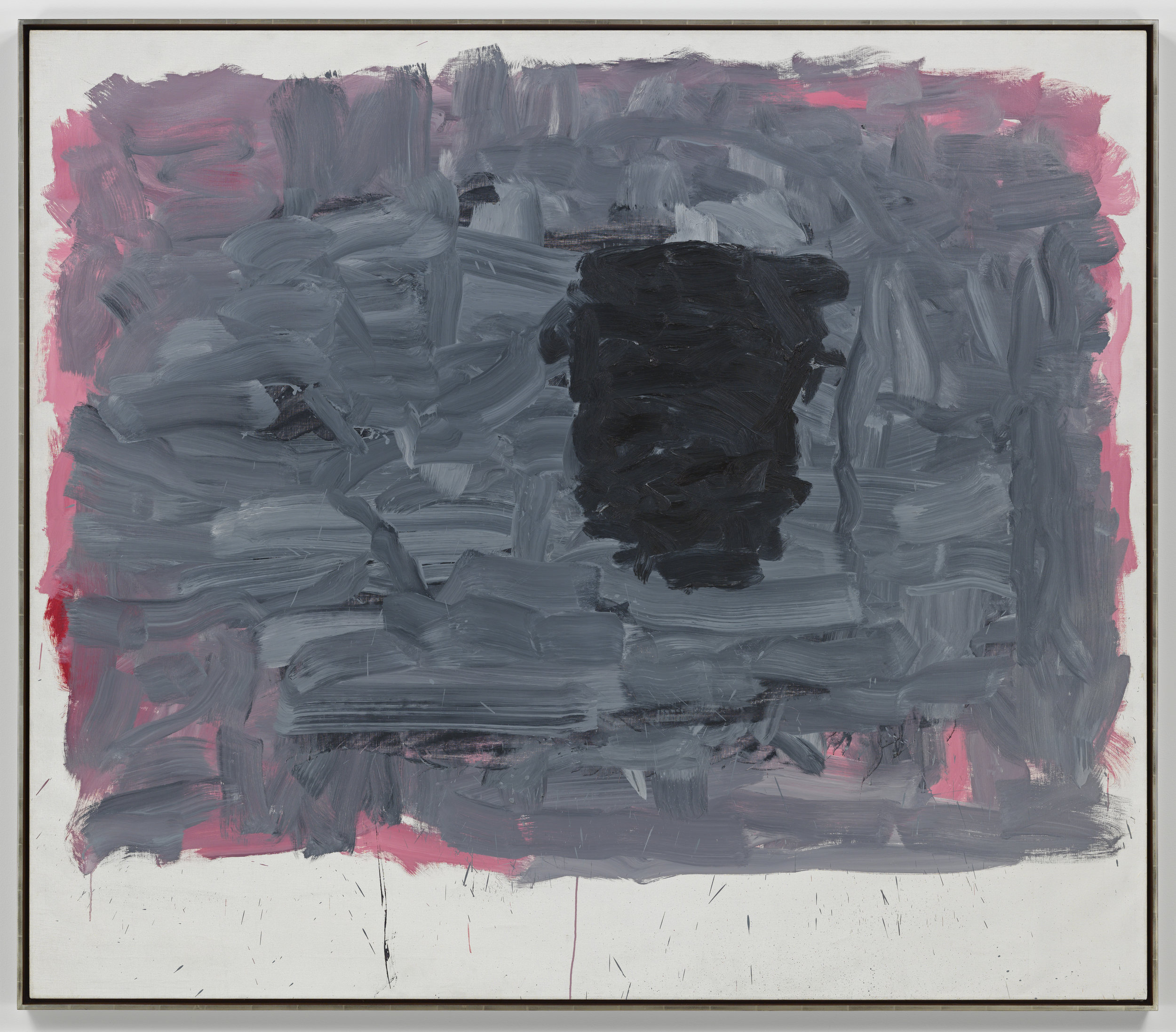

Sillman on the other hand is working out of Philip Guston among others, who himself was conflicted about abstraction and figuration and the absolute “mastery” evidenced by his canonical peers of abstract expressionist painters such as deKooning, Rothko, and Pollock (Figure 4). In Guston’s work, one is clearly confronted with his questioning of the dichotomy or the binary split of abstraction and figuration, and/or machismo and the feminine impulse. The use of underlying pink color against the grey forms signals his desire to bring two seemingly opposing sensibilities together, at once frivolous and solemn. What is interesting is that Sillman is considered a contemporary “feminist” painter who has synthesized the very struggle that artists such as Guston had with the opposition of abstraction and figuration. The blurring of the two was unacceptable in Guston’s time based on the masculine notion of singularity and its constant vying of supremacy between the two poles, which in itself has become obsolete today.

Figure 4. Philip Guston, Portrait I (1965). Oil on canvas, 68 3/8 × 78 inches (173.7 × 198.1 cm). The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

We can also see the feminine quality in the works of the abstract expressionist painter Kimber Smith (figure 5), who was very close with Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, and Shirley Jaffe, and who evidently was not supported by Greenberg at the time, because his works were not aggressive enough. In other words, they did not exude masculine qualities associated with certainty, stability, and mastery. Today these works can be seen as an important harbinger of things to come in abstract painting. While Smith’s paintings may not have direct stylistic influence, they signal an opening for challenging and de-stabilizing those qualities that modernism championed that we can see in the works of painters as diverse as Stanley Whitney, Charlene Von Heyl, Patricia Treib, Marina Adams, Richard Aldrich, Andrea Belag, and Amy Feldman, among many others.

Figure 5. Kimber Smith, Friday the Fourtheenth (1979). Acrylic on canvas, 64 x 68 inches (162.5 x 12.75 cm). Copyright Kimber Smith. Courtesy of the Estate of Kimber Smith, New York.

The question of the feminine is a male myth. It is a justification for a fear of becoming victim, and is tied to an impulse to subjugate. The conventional concept of the feminine rationalized the conflicted impulses of a patriarchal structure by suppressing all that would inhibit the drive to dominate. These impulses and characteristics have been assigned to those who are dominated. Creating a logical premise for ruthlessness, the logic of the ideology of the other is not difference, but a binary opposition. Such a way of thinking, e.g., the binary, either/or, with or without, can never realize itself, but in the most tense and false forms of formal equality, because the principle of respect and the concept of equality does not become revised. Instead it is continually negated. Rather than acknowledge that the principle of dominance and subordination is no longer constructive, there is often an impulse to reconcile the opposing forms of domination that would tolerate difference as a form of unjudgeable quality. This produces only stasis.

We are living in an increasingly conservative and dangerous world. Facts are being manipulated for the sake of dominance of world order regardless of human cost. In such an environment, the opposition between masculine and feminine and the construction of women’s selfhood becomes subsumed into the larger problem of organized oppression, but we must not distract ourselves of the urgency this puts on the ongoing necessity to establish a more credible relationship to the issue of female identity and how this can impact our society.

Let us not forget that trying to solve the riddle of the enigma of women is strictly a masculine pre-occupation. Women are not concerned with Truth for we know there is no such thing as Truth. Peel one layer or remove a veil and yet another exists, there is no way to eradicate the infinite layers that continue to appear. Such is Truth.

Notes

[1] These qualities are all at present fully accepted into the lexicon of abstraction with younger painters’ utilization of these approaches now bordering on conventions.

Author Bio

Shirley Kaneda is an abstract painter who lives and works in NYC. She has exhibited both nationally and internationally since the late 1980s. She has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Pollock Krasner Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts and the Elizabeth Foundation among others. She was Professor in the Fine Arts Department at Pratt Institute until her retirement in 2017.

References

Kaneda, Shirley. 1991. “Painting and Its Others, In the Realm of the Feminine.” Arts Magazine (Summer): 58–64.

Kofman, Sarah. 1985. The Enigma of Women, Women in Freud’s Writings. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Rose, Jacqueline. 2011. “Femininity and Its Discontents.” In The Jacqueline Rose Reader, 31 –47. Durham: Duke University Press.