Beauty marks: the Latinx surfaces of loving, becoming, and mourning | Jillian Hernandez

Abstract

There are few conceptual frameworks for tarrying with racialized gendered Latinx surface beyond analyses of representation. One entry point could be the beauty mark, the made-up face, and objects/materials such as glitter, nails, and rolos (hair rollers)—those surfaces and things that bind me in memory to my grandmother, and, by extension, to other women in my family as well. This text enacts a performative and theoretical exploration of the ontological contours of femme Latinx beauty practice to craft a poetics about the relationalities, recognitions, and femme generations that these surfaces engender. It juxtaposes authoethnographic prose that conjures the body work of the author’s grandmother with analyses of cultural production by Latinx artists Patricia Zambrano, Mujerista Market (Salina Zazueta-Beltrán), @anythingforselenaaas, Zahira Kelly, and others to evoke how making beauty marks haunts us, makes us possible, and brings us together in becoming, love, and loss.

Figure 1. Instagram post by @mujeristamarket, August 19, 2016. Model: Claire @Cacophonyyy. Image courtesy of Mujerista Market.

The pink is abuela’s erotics made properly blatant

Written inside the lips of a rose like a clit in patient waiting

But she made it shiny and enjoyed every step as she pressed her foot to the pedal of the sewing machine and felt the metal and chains rumble

She wore pants everyday but got her nails and hair done once a week

Aquanet filling in for the needed volume

Upright

Hair like a glossy contemporary sculpture

She hid anger in her beehive

And suffocated gender like the Virginsita she placed under the bell jar

Next to flowers, a dish of water, a candle, and pictures of her parents

She worked and learned English as a rebellion

It seemed that her bed was wrapped in the same cracked plastic as the couch but

Embroidered with roses

Standing in for her flesh

Flesh perfumed protected by pungent florals

The garden I took naps in

The plants that manifested her desire

I see my grandmothers in the Instagram posts of Latinx artists.

My seeing moves me to tell stories that place my abuelas, you, and me in the same place. So that we can see together, what knowledge of our racialized gendered Latinx surfaces can look like beyond analyzing representation.

How can we be in community and make it through together if you don’t see me and I can’t see you? Mandame un selfie por favor. Lo necesito para saber.

We can call this visual intimacy between us a methodology. Gloria Anzaldúa, una de mis abuelas de la teoría, gives me permission to let the images you will see here “speak to and through me, imagining my ways through the images, and following them to their deep cenotes, dialoguing with them, and then translating what I’ve glimpsed.” (2015, 4)

Moving from my family, to the artists, to me.

And then back again.

So that I can show you.

This is what she describes as writing with and not about images.

I write so that we can create an entry point out of the made-up face. A portal out of glitter, nails, and rolos. Those surfaces and objects that bind me in memory and performance to my grandmother, and to a universe of women, femmes, and queers of color. (Because we know that Reina Gossett’s eyeshadow is a galaxy.)

Whereas my previous work on embodiment and what I call sexual-aesthetic excess centered on the social politics of femme working-class Latinas coming into visual discourse in contemporary art, media, and the everyday. How they have been ridiculed, desired, and appropriated (but never fixed). Here I’m more interested in crafting a poetics about the relationalities, recognitions, and femme generations that these surfaces engender.

I write the poetry, prose, and stories here to let you in to my conversations with these artists, the images they create, and the women in my family because I need you to be a part of them.

I think our lives are at stake.

Mandame un selfie por favor.

Lo necesito para saber.

Andonde estas, y si estas con migo.

Everytime you pose for yourself, you pose for me.

The selfie is our poetic praxis, no? It has a long tradition. It used to be more collaborative.

You would take the picture for me.

But still – we made our own faces.

Now.

Instagram is the archive and the repertoire. (Taylor 2003)

The place where we write our surfaces into existence.

No solo en la representación.1

It’s where we perform the palimpsest.

Where your face looks like my grandmother’s looks like mine.

And so we love, mourn, haunt, heal, and become.

One of my grandmothers, the Cuban one, wears pants. The other, la Boricua, I never saw in a pair.

The one in pants married young and continues to be with the same man. The one in skirts didn’t marry until her late 50s, and I don’t recall if the relationship lasted to five years …

When I saw the image fashion designer Salina Zazueta-Beltrán of Mujerista Market posted on Instagram @mujeristamarket (Figure 1), it sparked the poem about my grandmother who wears pants.

Mujerista market’s rococo brown girl pink and voluptuous play with religious imagery was a cue. To take up my grandmother’s body (which means to write it). I’m grateful she’s still with me.

& I keep thinking about the other grandmother. The one we all called by her Bronx community theatre stage name, Madelyn, rather than her real name, Zaida. The one who I can’t call anymore. The one who I didn’t call enough. The one in skirts and never pants like me. The one who I mirrored so much it scared me away sometimes, I realize looking back.2

Born in Ponce, Puerto Rico in 1942. She moved to Chicago and then the Bronx. Union City, New Jersey, and then Miami.

I saw her once while visiting the Diane Arbus retrospective Revelations at the Met in 2005. I was looking at Puerto Rican Woman with a Beauty Mark, N.Y.C. of 1965 (Figure 2).3

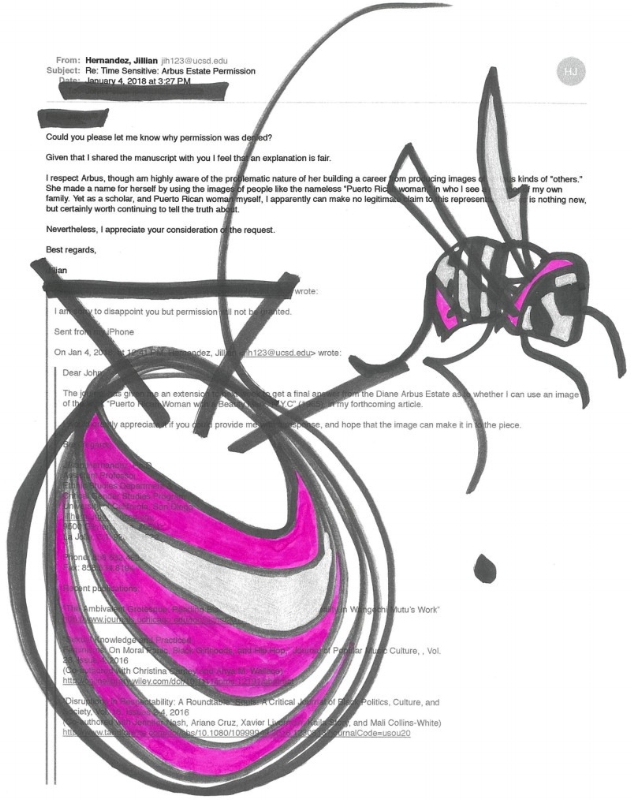

Figure 2. Jillian Hernandez, What the moon, the beauty mark, and the wasp told the Arbus Estate, 2018. Ink on paper. Image courtesy of the author.

The woman in the photograph looks so much like my grandmother and her sisters. And the beauty mark. The lunar. The moon surface that pulls other gazes in.

My grandmother was known for the one on her chin. The velvety mound that she had darkened with India ink, and that I then inherited in the same exact place with ambivalence.4

It made me feel like the type of Latina Diane Arbus typed. Like the type that typed Mario Montez within shame type but at the same time look at his luscious red lips type. That is also me. Without Warhol or Jack Smith. Or Crimp. Or even recoveries by Muñoz, Cruz-Malavé, and Oiticica. Without Conrad Ventur.5 Because we were femmes, and, so, this was something we could claim. Lunares for astronauts. The marks on our face.

Anzaldúa is right that the face is “the most naked, most vulnerable, exposed, and significant typography of the body” (1990, xv). But rather than unmask these faces to expose the subjectivities occluded by white supremacy and heteropatriarchy, I want to tell you that my grandmother’s máscara and mascara do genealogical work, in addition to performing what Anzaldúa names the power of Latina faces in saying “get out of mine” (ibid).

The beauty mark that my grandmother accentuated with permanent makeup was surface work that willed me into being.

Decades after that, my daughter was born with my mother’s petite Kusama dot6 of a birthmark on the edge of her upper lip.

This is one of our powers. Making worlds by bringing each other into them. And all we need to do is play with makeup, and pose.

“The queer thing is that we were born at all … The queer thing is that we were born; our young and/or deviant and/or brown and/or broke and/or single mamas did the wrong thing. Therefore we exist: a population out of control, a story interrupted” (Gumbs 2016).

We don’t need marriage or biology.

We don’t need the politics of pride and recognition in our confrontations with whiteness.

Though they have been useful.

When we lose each other. When we meet each other. When we love each other.

Our resource is meta-physical.

We have cosmetic altarities. 7

An ontology that stays on the skin 8

With no need to peek underneath

The beauty mark does its magic

Making faces makes generations of feminists and queers of color.

Slow death. Incarceration. Deportation. Can’t smudge us off.

“ … the viscosity of our excess grates across the surfaces we touch. As sissies, butches, and spectacles of high-femme fabulousness, we produce gendered performances of overt desire that rouse discomfort” (Rodriguez 2014, 3). In others. But.

Love

in us.

Pose for me.

Pose for me like visual artist Patricia Zambrano’s two grandmothers do (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Patricia Zambrano, Socorro y Reynalda (Para Frida y Chavela), 2017. Image courtesy of Patricia Zambrano.

Socorro y Reynalda lie on the ground in pleasure. Coquettish. Modeling for their queer granddaughter’s camera and becoming so in the process as they mirror Frida Kahlo and Chavela Vargas’s creative erotics. 9

“From my perspective, I have seen my grandmothers in more intimate scenarios than I have my grandmothers with their own husbands” (Zambrano 2017, 20).

Their portrait hung in Zambrano’s M.F.A. exhibition at UC San Diego in June 2017, where I cried remembering my grandmother Madelyn, and where she performed Ofrendx, a meditation on gender and family that had a Mujerista Market approach to inhabiting the religious icon surface to produce queer Latinx intimacies and genealogies.

Zambrano, dressed with the mantle of the Virgin Mary, surrounded herself with photographs of Virgins from her grandmother’s collection of over 1000 nativity sets, collected and culled together over the years from gifts and visits to second-hand stores.

“When my grandmother Socorro was pregnant with my mom, her first daughter, she ate two plaster statuettes she had in her house, one of the David and one of the Venus de Milo. She describes the desire to eat them as something she just had to do (‘se me antojaba a verla’). Her body craved them even though they were not food. She doesn’t remember how she broke them but she knows she did it on purpose. She says she ate the Venus whole, but the statuette of David, she ate all except ‘su parte’ (his penis). She says jokingly, that she respected that, and that it disgusted her. ‘Tu mama salio blanca, blanca, blanca’” (Zambrano 2017, 18).

Eating Western sculpture was Soccoro’s immaculate conception.

Another act of beauty magic.

In Ofrendx, amid the candles and the photographs, Zambrano worked the surface, performing public scenes of family healing that were punctuated by small acts such as cooking, singing, smoking, and putting on makeup. In one scene, she lay on the ground smoking a cigar, her Virgensita mantle turned into a blanket, she echoed the gesture of one of her grandmothers posing like Chavela Vargas, while her song “Que Te Vaya Bonito” played. Then, her sister Elizabeth lay on the floor next to her as her Frida (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Photo documentation of Patricia Zambrano’s performance work Ofrendx, 2017. Image courtesy of Erika Hirugami and CuratorLove.

This was later followed in the performance by Zambrano, alone in the scene, applying lipstick and repeatedly kissing a photo of her parents walking down the aisle at their wedding.

Queering it, queering it, queering it, with every pigmented lipsmack and pucker pressed to the glass. As if to say, I love you, but it is the abuelas who I see, and who see me right now.

When asked how she achieved her unique shade of penny red, my Puerto Rican grandmother reveled in keeping her method of combining two different shades of drugstore hair dyes secret. She never wore pants, as the diabetes made her legs thin and bruised. But she displayed her long patterned skirts on hangers about her bedroom like an installation. When she passed away in 2015, the first thing my godmother Chippie did upon hearing the news was text me a picture of an altar she created for my grandmother that included a portrait flanked by flowers and a candle, a jewelry display, makeup brushes, and lipstick. She was immediately invoked and re-materialized through her surface work.

The photo my godmother choose for the altar (Figure 5), like most of the iconic pictures of my grandmother, had been cut to remove a man, a former lover, from the image. A long-standing mujersita 10 surface practice. A declaration of whose marks matter in the end. 11

Figure 5. Photograph of the author’s grandmother with partner cut out.

Pictures of abuela keep digging up. (Here she is with me in Ponce in 1979 [Figure 6]).

Figure 6. Photograph of the author as infant with her grandmother.

She was the face of our family. Even (and of course) when in rolos. Like M. Tony Peralta’s pop art a lo Dominicano renderings of Celia Cruz, La Lupe, and Selena (homages to the women in his family) (Figures 7 and 8). He has lost his mother. And posts pictures of her on Instagram too @peraltaprjct.

Figure 7. Instagram posts by M. Tony Peralta. Images courtesy of M. Tony Peralta.

Figure 7. Instagram posts by M. Tony Peralta. Images courtesy of M. Tony Peralta.

Abuela Madelyn was an example. Of how to live alone as a woman. Of how to maintain beauty until one’s last days.

In the end, that was all she had. There was no property or inheritance to pass on. But her beauty was not significant because of that. It was indeed the materialization of her vitality.

If Ana’s silueta is the after-burn, then Madelyn’s body is the crackling flame. 12

As are those of my Latinx artists and Instagrammers.

A young Latinx based in Riverside, California who takes Selena’s name, the gesture of brown intimacy in doing for her (anything), 13 and creates mask-like makeup looks that are Chola-goth/Betty Boop tributes to her mother Gwen who passed away when she was a child.

She posts pictures of her mother to display and disseminate the haunting. The makeup is the healing work (Figure 9). 14 Beauty as a practice of mourning, a plastic play that allows one to continue to face life artfully. Recovering, but not forgetting, by transmitting the memory on the body (Taylor 2003). Performing the haunting as transformative knowledge that can build community (Gordon 1997). Magic you can buy at Walgreens for 99 cents. Wet n’ Wild. The kind of cosmetic curanderismo we learned watching Walter Mercado with our families on TV (Taylor 2003).

@anythingforsenenaaas sees herself in her mother, and others see themselves in her. Sparking transfers of recognition and relation (Figure 10). Her followers make portraits of her and those then get posted too. I scroll through these at night while breastfeeding my son to sleep. Thankful for the view. Thankful for their existence and the fuck Trump15 mujerista worlds they form by appearing on the surface of my cracked iPhone screen.

Instagram post by @anythingforselenaaas: “here 4 a good time not a long time.” Image courtesy of Selena Ruiz.

Instagram post by @anythingforselenaaas. Photograph with her mother as infant with the caption “your face will haunt me forever.” Image courtesy of Selena Ruiz.

@anythingforselenaaas is friends with Salina, the Los-Angeles based fashion designer of Mujerista Market, also friends with the artist and model @bellaferrada (of LA), who is also friends with the artist, rapper, and stripper @lagoonychonga (Figure 11). 16 When this coven of Latinx mujerismo reaches the 305-bred Lagoony, it takes me back home to Miami. Where my grandmother died, and where my mother and sister wait for me to return.

& meanwhile I play Princess Nokia’s “Brujas” here on the West side where I live because I hope her East Coast prima frequencies will get me home faster. Hit the road fast like her lip liner.

& pray. (with @bad_dominicana Zahira Kelly’s Afrolatina hands 17 [Figure 12])

Figure 11. Instagram post by @lagoonychonga, pictured here with @anythingforselenaaas and @auntyokaaay. Image courtesy of Lagoony Chonga.

Figure 12. Zahira Kelly, Praying Hands, 2017. Image courtesy of Zahira Kelly.

We only have so much time to be together here.

So trace the beauty marks to our family trees.

I don’t know these women but they know me.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to my grandmothers Zaida Santiago and Virgina Hernandez. I am grateful to Yessica Garcia Hernandez for thinking with me throughout the process of writing and to Uri McMillan for seeing the beauty in these marks. I thank the artists for granting me permission to reproduce their images here and for their life-sustaining work.

Notes on contributor

Jillian Hernandez is a transdisciplinary scholar interested in the stakes of embodiment, aesthetics, and performance for Black and Latinx women and girls, gender-nonconformers, and queers. She is currently completing her first book, tentatively titled, Aesthetics of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment, which is under contract at Duke University Press, and is working on a second book-length project on the erotics of Latinx cultural production. Hernandez teaches courses on racialized girlhoods, Latinx sexualities, theories of the body, and cultural studies at the University of California, San Diego in the Ethnic Studies Department and Critical Gender Studies program. Her scholarship is based on and inspired by over a decade of community arts work with Black and Latinx girls in Miami, Florida through the Women on the Rise! program she established at the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami. She has continued this work in San Diego in collaboration with Yessica Garcia and Hilda Gracie Uriarte through the creation of the Rebel Quinceañera Collective. Hernandez is also an artist and curator of contemporary art.

Notes

1. I am indebted to Yessica Garcia Hernandez for the insights in this section of text.

2. I write this as a guilty granddaughter. One who knows she could have done more to help her grandmother who lived alone for so long. But, with time and my own struggles, I've also come to understand her steadfast rejection of being helped.

3 The Diane Arbus Estate denied my request to reproduce this image in the article, which highlights the art world appropriation of femme Latinx embodiment and surface aesthetics I am calling attention to here. Although I see a member of my family in Arbus's depiction of a nameless “Puerto Rican woman,” I can make no legitimate claim to the image, her body. I created a drawing (Figure 2) that responds to the denial.

4 The ambivalence came from a feeling of shame. I recall feeling that it marked me as racialized, other. It was not the clean white surface I saw exalted in media as a child growing up in the U.S. in the 1980s. To me, it was the opposite of the beauty mark. This shame recalls Gloria Anzaldúa’s discussion of how “To be close to another Chicana [/Latina] is like looking into the mirror. We are afraid of what we'll see there. Pena. Shame. Low estimation of self” (1987, emphasis in original). Instagram can be a healing platform in its affirmative mirrorings of Latinx embodiment. I am referring to body-positive feeds like @chairbreaker and @nalgonapositivitypride. I am in wonder of how these surfacings generate new repertoires of embodied performance for young Latinx.

5. In this paragraph I am referencing how the meticulously made up, mask-like visages of femme Latinx like Mario Montez have an iconic, if nonetheless marginal, place in queer theorizing (Crimp 2002) and the wider historiography of queer white men’s cultural production. Whether they appear as spectacular bodies in the films of Jack Smith or Andy Warhol, or as striking, if exotically generic, impressions in works such as Diane Arbus’s Puerto Rican Woman with a Beauty Mark (1965), these surfaces have been worked to mark white artistic genius, while the aesthetic innovations of femme of color body work go unremarked or undermined. Latinx artists and cultural theorists have recovered figures like Montez from narrow readings of brown queer shame that refuse to acknowledge their complexity and cultural contributions (Muñoz 2014; Oiticica 2014; Cruz-Malavé 2007). And non-Latinx artist Conrad Ventur created a beautiful body of photographs, videos, and exhibitions with and about Montez titled Montezland. The work was created in 2011, after Montez’s performance hiatus of several decades, and shortly before his death in 2013 (see Montezland). These are important interventions. However, here I am interested in a mujerista gaze upon Montez and other Latinx queers, cis and trans femmes, and non-binary people. This is a vantage point that is missing in the engagements with Montez thus far, and that I plan to explore further in future work.

6. Shoutout to Ruth Nicole Brown for always reminding me of the endless potential of Yayoi Kusama’s obliterative power.

7. The presence of spirit, ancestor honoring, offering, and ritual that recurs throughout the practices I reflect on here exhibit what Laura E. Pérez names “the politics of spiritual and aesthetic altarities.” Altarities describes how Pérez views Chicana art production as “offerings on the altar where the material and the still disembodied are invoked,” where alterity is performed through spirituality, and where mujerista, non-Western ways of knowing are drawn upon (2007, 6). I like to see the dresser where makeup is applied, which in my grandmothers’ homes is not too far off from their altars, on the same plane.

8. My thinking on embodiment, skin, flesh, and surface has been shaped by the work of Fanon (1967), Spillers (1987), Cheng (2011), Weheliye (2014), Ochoa (2014), Thompson (2009, 2015), McMillan (2015), and Stephens (2014).

9. Zambrano’s photograph is based on a well-known 1945 photograph of Frida Kahlo and Chavela Vargas by Nikolas Muray.

10. For me, mujerismo is an epistemology, a queer and feminist politics, creative practice, ethics and mode of life that centers cis/trans/queer women and femmes of color. The spirit of the mujerismo that inspires me is exemplified by the queer Cuban Hip Hop group Krudas Cubensi (https://soundcloud.com/krudas-cubensi).

11. My grandmother’s ripped-up photos removing her male lovers remind me of the stories of Black mujerismo Anya Wallace tells about the grandmother in “Sour Apple Green: A Queer Memoir of Black Family.” “The Cousins always believed it was Mam’. Mam’ was the one that was so mean. ‘She probably drove Pop away,’ they would gossip. They had tried to imagine the stories that would fill in the pieces of her life that they did not know, would never know. She was secretive, iron-clad secretive. Asking her questions was out of the question. Like the time BrightEye boldly declared one day, ‘I’m gonna get married when I’m nineteen—just like you did, Mam’’. Mam’ shot the nastiest of looks, growling, ‘No you won’t. That’s the stupidest thing I ever heard.’” (2014, 1047: emphasis in original). Anya’s telling has inspired me to write this. Especially as my grandmother Madelyn was similarly characterized among my siblings as the “mean” grandmother due to her non-conformist performances of gender.

12. Here I reference José Muñoz’s framing of artist Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series of earth-body performance works, which used materials like fire and blood, as “the after-burns of mimetically generated intensity … stagings and renderings of élan vital that manifested the ontological force of brownness as a mode of particularity in multiplicity” (2011, 193). Muñoz reads Mendieta’s work persuasively as highlighting the after-burn of brown vitality, “death-in-life as something like a mystical force” (ibid.) I understand my grandmother’s beauty markings, centered on her face (like Mendieta’s facial transformation works), as a force that kept her alive as a poor, diabetic, brown, Puerto Rican single mother. And as a force that creatively brought my mother, my daughter, and me into being.

13 As performed in the popular scene of the Selena biopic (Nava 1997) where two cholos help Selena get her tour bus out of out a ditch on a remote road (on YouTube). “Anything for Salinas!,” the cholos say as they eagerly try to get the bus out of the rut. It was this phrase that I found myself recalling the night Trump won the 2016 election. It was a reminder to myself and a call for solidarity, for Latinx to (continue to) take care of each other.

14 The practices of posthumous mimicry @anythingforselenaaas performs recalls Deborah Paradez’s theorizing on how embodying Selena for Latina girls and queer Latinx constitute modes of affirming and healing Latinx identification (2009).

15. Latinx creative and model Isabella Ferrada has been designing and selling Fuck Trump T-shirts following the election (Remezcla)

16. The relationships and cultural politics these artists are creating have been recently profiled by Vogue magazine (Vogue)

17. Zahira Kelly is an artist, cultural critic, and social-media activist who centers issues of Latinx anti-Blackness, coloniality, and sexism.

References

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1990. “Haciendo caras, una entrada.” In Making Face, Making Soul/ Haciendo Caras: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color, edited by Gloria Anzaldúa, xv--xxviii. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 2015. Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality, edited by Ana Louise Keating. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Cheng, Anne Alin. 2011. Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Crimp, Douglas. 2002. “Mario Montez, for Shame.” In Regarding Sedgwick: Essays on Queer Culture and Critical Theory, edited by Stephen M. Barber and David L. Clark, 57–70. New York and London: Routledge.

Cruz-Malavé, Arnaldo 2007. Queer Latino Testimonio, Keith Haring, and Juanito Xtravaganza: Hard Tails. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fanon, Frantz. 1967. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove.

Gordon, Avery. 1997. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Gumbs, Alexis Pauline. 2016. “m/other ourselves: a Black queer feminist genealogy for radical mothering.” In Revolutionary Mothering: Love on the Front Lines, edited by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, and Mai’a Williams, 19–31. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

McMillan, Uri. 2015. Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance. New York: New York University Press.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 2011. “Vitalism’s after-burn: The Sense of Ana Mendieta.” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 21 (2): 191–198. doi: 10.1080/0740770X.2011.607596

Muñoz, José Esteban. 2014. “Wise Latinas.” Criticism 56 (2): 249–265. doi: 10.13110/criticism.56.2.0249

Nava, Gregory, dir. 1997. Selena. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.

Ochoa, Marcia. 2014. Queen for a Day: Transformistas, Beauty Queens, and the Performance of Femininity in Venezuela. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Oiticica, Hélio. 2014. “Héliotape with Mario Montez (1971).” Criticism 56 (2): 379–404. doi: 10.13110/criticism.56.2.0379

Paradez, Deborah. 2009. Selenidad: Selena, Latinos, and the Performance of Memory. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Pérez, Laura. E. 2007. Chicana Art: The Politics of Spiritual and Aesthetic Altarities. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Rodriguez, Juana María. 2014. Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings. New York: New York University Press.

Spillers, Hortense. “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book.” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987): 65–81. doi: 10.2307/464747

Stephens, Michelle Ann. 2014. Skin Acts: Race, Psychoanalysis, and the Black Male Performer. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Taylor, Diana. 2003. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Thompson, Krista. 2009. “The Sound of Light: Reflections on Art History in the Visual Culture of Hip-Hop.” The Art Bulletin 91 (4): 481–505. doi: 10.1080/00043079.2009.10786149

Thompson, Krista. 2015. Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice. Durham: Duke University Press.

Wallace, Anya M. 2014. “Sour Apple Green: A Queer Memoir of Black Family.” Callaloo 37 (5): 1042–1050. doi: 10.1353/cal.2014.0215

Weheliye, Alexander G. 2014. Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham: Duke University Press.

Zambrano, Patricia. 2017. “Ofrendx: Yo tambien se curar (I, too, know how to heal).” M.F.A. Thesis. University of California, San Diego.