General Sisters, General Store | Liz Park

General Sisters, General Store

A Conversation

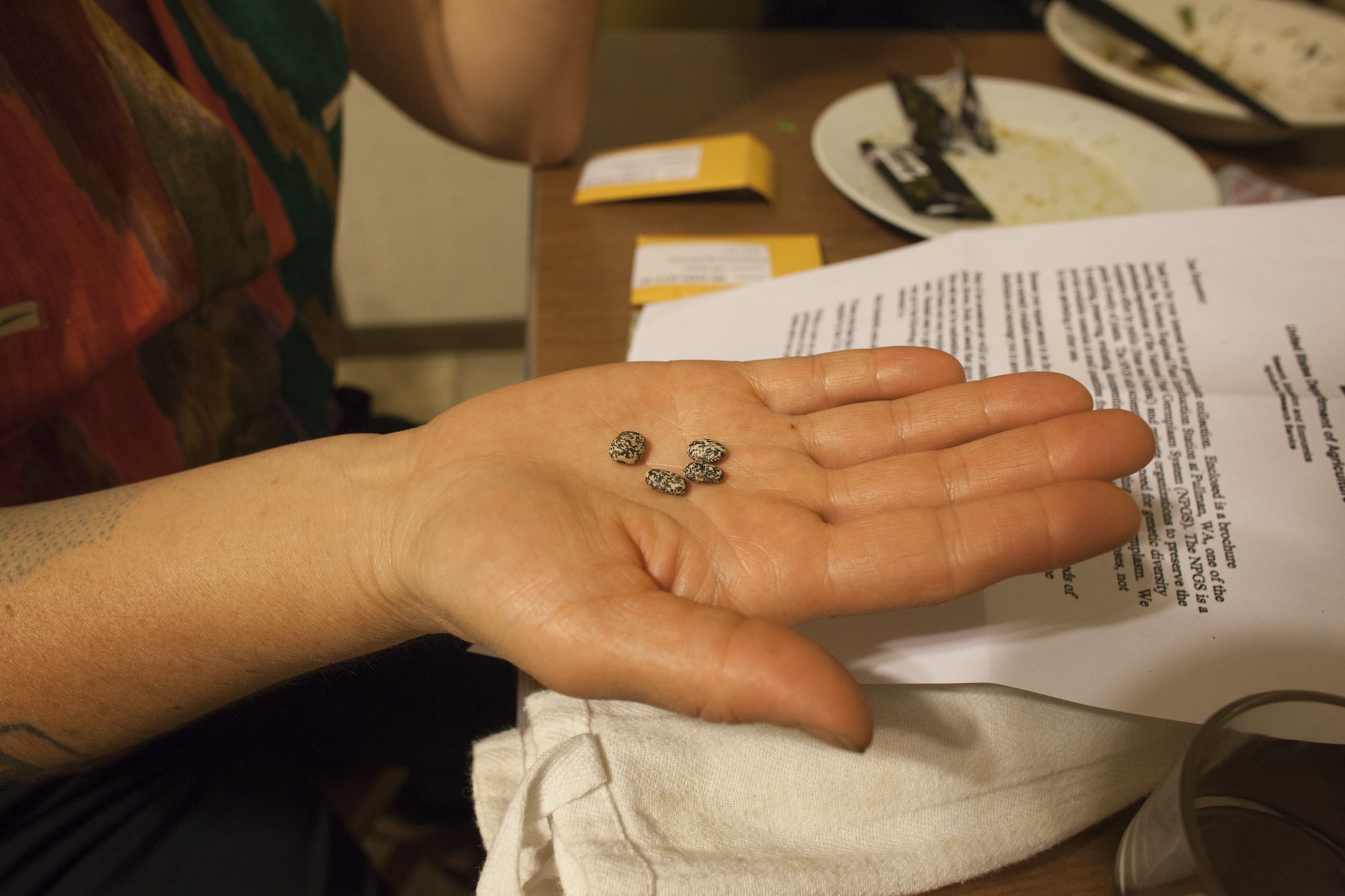

Dana Bishop-Root and Ginger Brooks Takahashi have been working to open a shop called General Sisters, General Store in a historic steel-mill city of North Braddock, Pennsylvania. Since 2012, they have been cultivating a healing garden where food, conversations, medicine, and ingredients grow while restoring the building of a former grocery store. General Sisters is a long-term rebuilding of a place of gathering in the rustbelt region of Pittsburgh. On April 10, 2017, I visited Dana and Ginger in Ginger’s home in Braddock, where we shared their unique version of Passover Seder. Colter Harper joined us to photograph our meal.

In advance of our meeting, I asked them to prepare a menu that is representative of General Sisters. “What flavors and conversations do you want us to enjoy through this menu?” They prepared:

- spring somen with mint and bee balm ice

- hops tips with puff ball powder

- dandelion buds in hazelnut turmeric dukkah

- nettle ohitashi with sesame

- apricot and apple charoset with baby horseradish greens and nasturtium vinegar

- dandelion flower Old fashioned

On the Menu

Dana: We got excited by the prompt to make a menu for Liz. That’s how we think about food, who we’re making it for. Then we think about what’s happening around us. We decided to use vegetables that are growing right now in our spring garden. We did a walkthrough of the garden this morning and looked at what work needed to be done to prepare the beds to wake them up, and see what was ready for our meal.

Ginger: During our walkthrough we were talking about weeding. Some of the plants we’re eating here are considered weeds, for instance, these nettles and dandelions. It’s interesting to examine human constructs of plants.

Dana: Another aspect of the meal is that it’s Passover, so we made some charoset. Charoset on the brick represents the physical labor that we do as part of General Sisters. Usually, you’d have Charoset on matzo with horseradish, the ground root, but instead we have the sprouts here.

Ginger: Typically matzo cracker would be used to represent the brick. We’re literally using the brick to represent the labor.

Dana: The somen is inspired by Passover and the process of dipping parsley in salt water to think about tears. The herbs in the noodle are clary sage, yarrow, sorrel, collard greens, purple sage, and garlic chives.

Ginger: It’s also inspired by the Korean noodle dish with dongchimi [radish water kimchi], and is unintentionally related to a Persian New Year dish of green noodles. The tangling and the untangling of noodles are about letting go of your troubles.

Dana: These are hops tips with foraged puffball mushroom powder with Korean red pepper flakes from last season. These are dandelion buds with hazelnuts that we grew and turmeric.

Ginger: This is nettle ohitashi with sesame dressing. If you encounter nettles in the wild, these hairs will sting you but these have been blanched, so the stinging part is removed for us.

Liz: What percentage of your own harvest is used by General Sisters?

Ginger: In terms of our intention, inspiration, and symbolically, 100%. But it depends on whether it makes sense for us to use our harvest.

Dana: When we’re preserving things or making salt, we can change the scale of what we grow. For a meal like this, with all these micro greens, it’s about our labor. A lot of what we grow is medicinal, so it’s a question of how we use what we grow.

Ginger: Dana and I have a different relationship to foraging. One of the things I learned from Dana is to not assume a consumer relationship to plant life. The plant world is there for itself. It’s a very human-centric perspective to ask can I eat it? At the same time, how can I use it is an important question.

Liz: Consuming something is one way in which you are porous with nature. The question of cultivation is often around how to industrialize/scale it up.

Dana: Also, what’s sellable has to be good looking. If we didn’t have an attachment to how we think carrots should look, for instance, then how much farther could carrots go?

On mothers and inspirations

Dana: My mom is a biologist and what I do is influenced by how I was raised. Recently, we went on a four-hour hike and we were looking at everything. I felt like I was consuming so much—a visual consumption that allowed me to interact with the biodiversity and be part of it as opposed to needing to ingest it.

She taught for 40 years. She’s currently working for a grassroots conservation organization for hardwood forests in Indiana because Mike Pence sold all of the wood in the state forest to private timber companies. She was telling me about a student she met who was studying compassionate conservation, which promotes the idea that ultimately there’s nothing that we can’t be compassionate about. There’s no such thing as invasive plants, or something we don’t want. Part of understanding biodiversity in this way is to take away human constructions and tendencies to anthropomorphize.

Ginger: I went to Silvia Federici’s talk at Carnegie Mellon University recently, and she was talking about the commons as a place where people can graze stock and gather water. Once the lords started fencing in, it started changing the people’s relationship to the land and their labor—the first mark of privatization. I was thinking about the model for state forests as commons but at the same time, it isn’t at all.

Liz: I want to hear about Ginger’s mom too because I sense strong maternal lineages to this collaboration.

Ginger: When I was leaving my mom’s place last week, she packed me a container of shiso leaves she had grown and pickled from last summer—all stacked up with chilies between them. She pickles the seeds too. She’d put them on the platter raw with some fish.

Liz: Your mother grows a lot of food for herself?

Ginger: I grew up with a small garden of edibles, which probably started with Asian vegetables that she couldn’t find at the store. I also grew up foraging with her—fiddleheads, wild fruits, but never mushrooms.

Liz: Did you learn a lot of the culinary techniques from her?

Ginger: Yes. I grew up cooking with her. We both like to explore different traditional food. Sometimes I will get stuck in traditions. Dana would suggest variations on a Japanese dish and I’d say, I don’t know about that.

Dana: I wanted to use Swiss chard for ohitashi instead of spinach.

Ginger: That was a major hump! It might be my cultural baggage of being biracial. Not being fully one thing, I want to do the real thing and honor it. I think that’s how I justified it.

When I brought my mom a bag of chive tops from the greenhouse where I’m growing onions, leeks, and chives, we talked about what kind of food we’ll make with these. She said what kind of okonomiyaki are we going to make? Japanese kind? Because the Japanese don’t make okonomiyaki with chives. So we got to laugh about that.

On collaborations

Liz: Sisters, how did you begin this collaboration?

Ginger: When Dana moved here, she was thinking about possible jobs and was interested in working at a grocery store. Thinking about the grocery store as a place of choice, abundance, and scarcity brought up questions about intimacy around consumption.

Dana: You can look at Braddock and say that there’s no grocery store but you can also look at the place as having many small economies that supply food for people. I got excited thinking about a place to buy food that activated choice in a tangible and explicit way. So I started this dream of opening a general store.

In 2012, there was a building that was offered to me by a plumber. He became too old to maintain it. He heard about the grocery store idea. He said, “This place used to be a grocery store until 1976. I’d really love it if it can be a grocery store again but you need to pay back taxes on it and fix the roof.” So we got together with Ginger’s friends and we learned about roofing by taking it apart.

Also, the dominant way of experiencing things in the neighborhood is by having to let things fall apart. That’s seen as blight, something negative that symbolizes socio-economic history and deindustrialization here. Instead, starting to take things apart was exciting to us and our neighbors, because it was a way to learn, as opposed to something out of control.

Ginger: So that’s how we started—building a roof together. We learned of a technique of strengthening old beams called sistering. Take new beams and sandwich an old beam, or put a new beam next to an old one, and bolt them together. When we were strengthening these beams, we wrote the names of different sisters on the inside and built them into the architecture.

Dana: Some of the names we painted on the outside of the building are on the inside too. They came from conversations we have about our collaborations. We wanted to recognize multiple authorship beyond ourselves. We started by making prints of different people that we feel our work was authorized by–Judith Butler, Angela Davis, etc. We’re creating a canon for ourselves.

Ginger: It’s a way to connect the work we have been doing in the garden outside to the work we’ve been doing inside the building. To connect visible labor with invisible labor, our inspiration with our politics.

On art and audience

Liz: Let’s say someone comes to an event that you cater and enjoys the food without recognizing your work as an artistic practice. Or, the store’s open and neighbors patronize the store without recognizing it as an art project.

Ginger: That’s not important. When we first started writing about the project and working on grant proposals, we were making a political decision. We were asking who’s eligible for arts funding, and how that changes our relationship to our neighbors.

Dana: We tried to apply to arts funding and failed. The funders would say that they are worried about the sustainability.

Ginger: I think it’s hard for arts funders to accept that it’s not important to us that it’s not always seen as art.

Dana: For me and Ginger, art has been the most accepting place for the work that we’re doing. None of our projects set out to declare that they are art but they engage with existing art discourses.

Liz: Do you find it more difficult to talk to people in the art world than it is to talk to people in the neighborhood who are not in the art world?

Ginger: I don’t think it’s harder or easier. I don’t think I frame it differently either.

Dana: It’s not hard to just speak about what you do. We don’t have to frame it differently to share that but it’s about how people respond to it.

On the General Store

Liz: How are things going with the building?

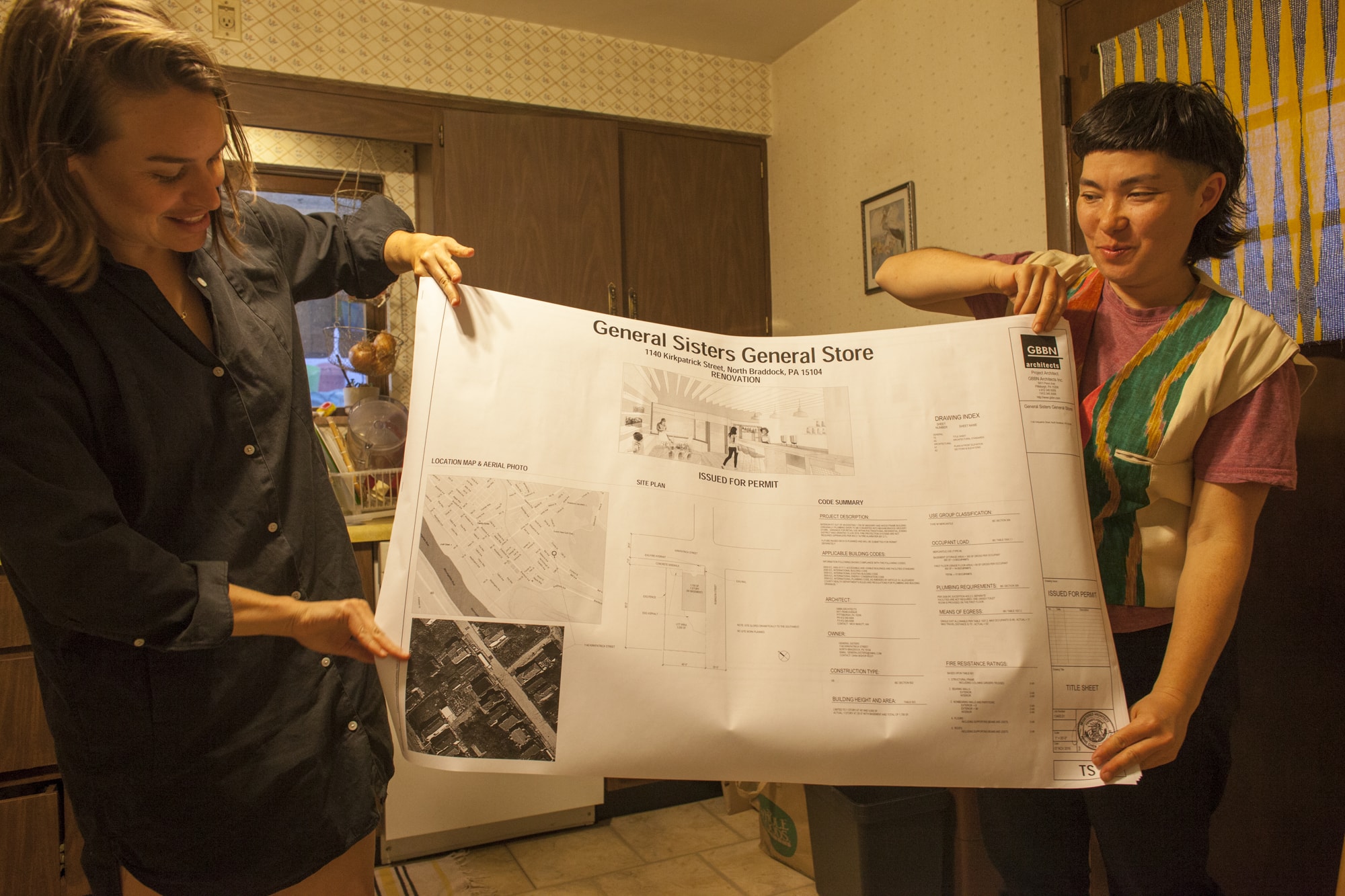

Dana: The architect who is volunteering for us finished our permit drawings! Now that means we can get an official permit. Our life got more complicated because of fracking in the area. We’ve been in a two-year holding pattern.

Ginger: This plan shows where our building is in relation to the lot, and describes things like plumbing and accessibility requirements and how we need to design bathrooms and the overhead view.

We’ve been waiting for more than half a year for this. We thought we had to give up a lot of times. The architect has very generously done all the work pro bono but that meant that we couldn’t impose a deadline.

Dana: Once the borough became more demanding about the way we did things, we really understood how the economy around this process worked. For instance, if we had to hire an architect to do this kind of plans, it would have killed the project.

Liz: Can you talk about some of the challenges you had to work through and are still tackling?

Dana: We had a contractor who took $14,000 from us and didn’t do any of the work.

Ginger: We received a very generous financial gift and that money went straight to this contractor. We even got a non-profit organization to be our umbrella to do accounting for that money. It was so embarrassing. That was five years ago.

Then, around the time that fracking was a real threat here, a lot of the residents got together to organize against it. There was some contention on the council but most were against it. A lot of the property here got rezoned as a result of the borough trying to protect them from potential industry.

Dana: North Braddock had never had zoning laws for 123 years. The volunteer lawyer who was helping us fight against fracking made the suggestion that the best defense we had was to pass the zoning ordinances as quickly as possible. That way, there’s no industrial zoning areas except for where the steel mill already is. For instance, it wouldn’t allow the golf course to allow fracking unless they appealed for zoning variance, which is a process that we can then fight. At that moment, we knew it would create a challenge for us, because it’d put the zoning ordinance through that made General Sisters no longer commercial in a residential neighborhood.

Ginger: We were also told that rezoning General Sisters to commercial use would be easy. What ended up happening was that we were punished for our activism by the municipality.

Dana: Not the council, but the people who work for the municipality that were enforcing these rules hade made the process really complicated. So we had to hire a lawyer. They have never had a hearing of this kind in the whole history of Braddock. As Ginger said, it felt like a punishment. We had to reconcile spending money that we saved on this lawyer.

We were setting precedence, because asking for variance in zoning had never happened in North Braddock. We hired a lawyer. She was awesome. A lot of people came to the hearing. At every turn, every challenge, the support from our neighbors makes us realize we have a deeper commitment than ourselves. That was an affirmation, but there was a lot of shame involved.

Ginger: When friends come to visit and ask what’s going on with General Sisters, we have to tell them that we’re literally at the same place.

Dana: There is shame because of people’s perception of where we should be. It’s really embarrassing that we spent all the money on the contractor, and on the lawyer instead of on the building.

Liz: I knew you before I learned about the store. So, for me, General Sisters is the two of you, and your collaborative process and practice precede the physical space. But hearing you speak about how the physical space precipitated your project, I understand the importance of the store as a place to dream and to think about the place you’re creating.

Dana: Yes, especially in a neighborhood where it’s hard to dream because you don’t want to create false ideas/promises. But I think everyone can dream about this store.

Liz: It is also political. There are so many people volunteering their labor. It’s a collective dream.

Dana: I value the slowness. It’s interesting to ask where the shame comes from. From ideas of success and ideas of how fast we should move. From my existence as a white person in the neighborhood and thinking about the roles of different economies, assumptions and exceptions apply to me because of my whiteness. I have invitations to some places and non-invitations to others. I think that our slowness has allowed a different language to be built in conversations that exist and are rooted in the construction of race here. It’s not just about development and redevelopment but how fast things move and how people participate or not in the evolution of something. Slowness can bring about a realistic version of how we create something together.

Liz: How do you see your collaboration changing with the opening of the store? I imagine that there will be a whole slew of challenges that come with operating a store that will change, I think, the nature of your collaboration.

Ginger: Logistically, it will change, because there will be other people who we’re going to be directly working with on a regular basis. I’m thinking of people will staff the shop (not necessarily us). They will add to the recipe of what will happen in the space.

Dana: The evolution of a collaboration is so important. For a while, we haven’t allowed ourselves to talk about the actualities of the store and how it will be because we have been waiting for this permit. So it’s a conversation that will happen really soon. Something that we share, however, is not separating administration from what we do. Making a budget can be just as beautiful.

Ginger: Yes, because it talks about our intentions and values.

Dana: General Sisters was always about creating a store/ food source and if the neighborhood utilized it and wanted to participate in it, then it would continue to run. If the neighborhood isn’t interested in sustaining, then it wouldn’t need to exist, and that’s okay. What will exist, though, is a building with a new roof and infrastructure–electrical, insulation, and plumbing—so if it needed to become a barbershop, for instance, it’d make perfect sense.

It was never about it being one thing forever. This is an idea and once it exists, we’ll see how we can support it. When people talk about being able to afford houses and buildings in North Braddock, it’s really not true unless you already have large amounts of capital or access to capital. Having a building that can be sold for fairly assessed value was very appealing. We made it as part of our operating agreement that we’re not going to sell it in the market and that it has to be for a neighborhood use.

Liz: Your project is specific to this place and there was a perfect storm of characters and events that led you to this. Do you see something like the General Store taking root elsewhere?

Dana: If we lived in New York, or a city that had a different kind of economy, we wouldn’t be able to do it in this way. That allows for a different kind of initiative. But something like General Sisters taking root in any place? Yes. People create different kinds of neighborhood markets and stores for that reason.

Ginger: Thinking about the needs of a group of people—geographical or ideological— there are lots of models for that other than a grocery store.

On agency

Liz: The project and the approach speak to your self-determination and agency. But there are situations that make the exercise of agency difficult—the hurdles that you’ve come across, for instance.

Dana: The practice of talking about agency resists ideas around how systemic oppressions and structural poverty are created. The lack or the removal of agency is the number one ingredient in how systemic poverty can exist. To include agency in our vision is utopic, in the way José Esteban Muñoz says, “Queerness is not yet here.” The way I use agency is that it is not yet here. It does not yet exist in the way that it’s towards liberation.

People face bureaucracy everyday. For instance, single moms who figure out how to get childcare. The system is there to remove agency. So are the cereal boxes with different packages containing the same ingredients. You’re not really making a choice if you’re stuck choosing the cheap one. There’s also false agency.

Ginger: I would also jump to the use of language around food and connect that to how a lot of agency can be removed from you.

Dana: For instance, calling a place a food desert. There’s a lot of violence in that. I see a fragile system that is being maintained in order to not see things and uphold other systems. But they can be blown apart easily when you start activating terms such as agency. Through conversations, we can expand on the practice and traditions of building knowledge together.

Liz: There have to be activations, sparks that start a conversation. That’s where food and flavor come in.

The art museum’s white cube is a looking device. Like a microscope, it sets a field of vision to focus on one thing—viewing art. So in that environment, it’s easier to activate an object or experience as art. But outside of the white cube, it’s so much harder because of all the distractions of the everyday life. So the activation needs to be more intense or evocative, or operate in a different way. I think of General Sisters as activators of food, memory, and conversations.